PHOTO: JUSTIN HAYWORTH © 2007/THE DES MOINES REGISTER AND TRIBUNE COMPANY. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION.

Before the fall: Lance Armstrong pedals Iowa’s open roads during RAGBRAI.

PHOTO: JUSTIN HAYWORTH © 2007/THE DES MOINES REGISTER AND TRIBUNE COMPANY. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION.

Before the fall: Lance Armstrong pedals Iowa’s open roads during RAGBRAI.

U nder a merciless July sun, Lance Armstrong appears around the corner of his Livestrong bus to greet starry-eyed Iowans united in their passion for cycling, camping, and cold beers. This is RAGBRAI 2011—and their hero has come to ride.

In hallmark black-and-gold jersey and sleek shades, Armstrong mingles with his admirers, shaking hands, signing T-shirts, and posing for photographs. Cycling is huge in Iowa and seven-time Tour de France champion Lance Armstrong is as huge as it gets. In his fourth visit to the state’s annual summer sojourn, Armstrong spends the next few hours biking from Carroll to Boone, where he will receive another warm celebration of his fame and philanthropy.

Longtime rider Steve Isaacson told the Des Moines Register at the time that he’d probably logged 650 hours on RAGBRAI, but the most exciting three seconds came when Armstrong blurred past. "Lance Armstrong is an American hero," Isaacson said. "He stands for everything that is great about the sport of biking."

Armstrong seemed to wholeheartedly enjoy Iowa’s cheer and hospitality that summer, despite more doping allegations that cast an ominous shadow. Still, he remained steadfast in his denial that he’d ever used illegal performance-enhancing drugs. Then, not two years later, the legend of the epic super-cyclist came to the end of the road.

Last January, on the Oprah Winfrey Network, Lance Armstrong sat disgraced—stripped of his Tour titles and banned from elite competition by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency. Dressed in guilt and a blue-gray suit instead of smiles and spandex, Armstrong finally made his confession to the world.

He was a cheat.

"The story was so perfect for so long—a mythic, perfect story that wasn’t true," said Armstrong, an exhausted look on his face. "[It was] one big lie I repeated a lot of times.... I am deeply flawed, deeply flawed. I deserve this."

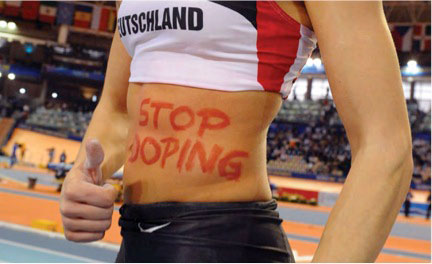

PHOTO: GERO BRELOER/PICTURE-ALLIANCE/DPA/AP IMAGES

A track and field athlete from Germany makes a statement at a world championship event.

PHOTO: GERO BRELOER/PICTURE-ALLIANCE/DPA/AP IMAGES

A track and field athlete from Germany makes a statement at a world championship event.

Lance Armstrong’s spectacular fall captured international attention, but he’s certainly not the only hero biking, running, and tackling with feet of clay. Sadly, doping appears the modern epidemic in today’s sports culture, and the Myth of Lance Armstrong is but one story that begs some soul-searching about the widening chasm between winning and personal integrity. Why is this happening and what of the future? These questions occupy the thoughts of athletes, fans, and anyone who ponders the individual and societal pressures at play— including sports medicine and mental health experts at the University of Iowa.

Work hard, win with dignity, lose with grace: sport has long been tied to crucial life values aimed at character-building. Yet the drive to gain an unfair advantage is as old as the early Greek Olympics. In those ancient days, athletes turned to performance-enhancers like exotic herbs and animal testicles to obtain an edge. Today, steroids, human growth hormone, amphetamines, and testosterone are many athletes’ drugs of choice and the proliferation of these substances among elite athletes appears to have reached a new plateau.

In January, shortly after Winfrey broadcast Armstrong’s interview, Major League Baseball’s leading sportswriters declined to vote famed sluggers Barry Bonds, Sammy Sosa, and Roger Clemens into the Hall of Fame—largely due to careers tainted by allegations of performance-enhancing drug (PED) use. Then, fresh doubts surfaced about New York Yankee Alex Rodriguez’s link to human growth hormone for its synthetic, muscle-building properties. Around Super Bowl time, Baltimore Ravens star linebacker Ray Lewis faced accusations that he had used a new sensation called deer antler spray, which contains a banned growth hormone. The same rumors surfaced about pro golfer Vijay Singh.

Even a familiar Hawkeye name recently made the news: the New York Giants suspended former Iowa football player Tyler Sash for testing positive for Adderall, an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication prohibited by the NFL for the unnatural level of mental sharpness it gives athletes. Sash maintained that a doctor had prescribed him Adderall for anxiety.

To achieve his phenomenal success, Lance Armstrong turned to blood doping, a technique that can involve transfusions and the injection of a glycoprotein hormone called erythropoietin (or EPO) to boost oxygenation of the blood and improve endurance. A systematic, international doping ring helped perpetuate a complex network of lies throughout Armstrong’s career, including repeated attempts at the unforgiving Tour de France race.

"In your opinion, was it humanly possible to win seven Tour titles without blood doping?" asked Oprah in her television broadcast. Armstrong, who now faces a U.S. civil fraud lawsuit as a result of his drug use, sighed: "In my opinion—no."

Then, he named the fatal flaw that brought him to this shame: the ruthless desire to win—and an unflinching willingness to risk it all.

UI sports medicine director Ned Amendola says that’s the world we live in, a world where many athletes consider doping part of the job. "The pressure to win, the desire to win—I think it’s insatiable," says Amendola, illustrating his point with a startling anecdote from the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games.

Doping scandals at the Olympics are about as perennial as any other enduring aspect of the Games. In Atlanta that year, athletes received a survey that asked whether they would take a performance-enhancing drug if it meant a guaranteed gold medal but also permanent side effects to their health. One hundred percent said they would. Another question asked if they’d take the drugs to win gold, knowing that doing so would eventually kill them. Fifty percent still responded yes.

"When you get to that level of elite competition," says Amendola, who also helps oversee Iowa’s in-house drug testing program for student-athletes, "you do want to win at all costs."

After all, to many athletes, success is their legacy—the sum total of their lives. In a fugue state that combines an intense drive for fame, the ability to rationalize the irrational, and a supreme sense of invincibility, some athletes will do whatever it takes to reach the heights of their sport. Plus, they compete in an environment unabashed in applying big bucks toward its cheating industry. They ignore the serious physical or mental consequences of illegal drugs, including heart and other vital organ problems, infertility, psychosis, and even death.

“Like all cheaters, they wanted to be somebody and couldn’t do it the regular way.” Gary Gaffney

Cheating athletes also don’t seem deterred by the potential loss of their reputations and accolades. Canadian runner Ben Johnson ran a jaw-dropping 9.79-second 100 meters for the gold in the 1988 Seoul Olympics; three days later, after he tested positive for the steroid stanozolol, Olympic officials stripped him of his medal and world record. In 2007, another celebrated track star, Marion Jones, finally admitted using steroids, EPO, and other PEDS and subsequently had to return the three gold and two bronze medals she won in Sydney seven years earlier.

"Like all cheaters, they wanted to be somebody and couldn’t do it the regular way," says Gary Gaffney*, 77BS, 81MD, 86R, UI associate professor of psychiatry and creator of the blog "Steroid Nation" (http://grg51.typepad.com), an online journal that examines PED use among athletes and others, often featuring commentary and observations about the latest news. A self-proclaimed "cheater hater," Gaffney started the blog about six years ago because the topic interested him as a sports fan, the father of an athlete, and as a professional who’s treated patients living with mental consequences like paranoia and suicidal tendencies stemming from PEDs.

Within the pervasive problem of cheating lies an interesting conundrum, Gaffney says. While elite athletes act out of their own personal failings and self-imposed pressure, they’re also influenced by a society bent on hero worship. Fans thrill at long home runs and that last bullet-pass on fourth down, cheer for sprinters who blaze down the track, and dab their eyes as they watch inspiring stories about the best of the best on ESPN SportsCentury. On a practical level, Gaffney says, it’s pretty difficult for a professional football star to stop doping when the "penalty" for their prowess can be a $50 million paycheck.

Yet, while sports enthusiasts love to bask in the glory of their favorite athletes, they still want a fair playing field. Often, the public turns a blind eye to suspected PED use and the intoxicating influence of money, but outrage pours down when dirty secrets inevitably surface.

"It’s funny how humans have this internal conflict," Amendola says. "Our nature wants to believe athletes—and we do as long as they’re hiding the truth. When we find out, we’re really upset." Suddenly, our heroes become villains.

But are they? Human beings are complicated and imperfect. Part of Lance Armstrong’s multi-faceted story includes more than $400 million he raised as an advocate for cancer survivors through the Livestrong Foundation. As someone who has worked on an oncology unit, Iowa City psychiatrist and ethicist Janeta Tansey, 99R, 08PhD, says it’s profoundly disappointing to realize the moral flaws in someone who provided inspiration and faith to critically ill people during times of great darkness. Like Gaffney, though, she’s also worked with patient-athletes who have made such ill-advised choices—and she knows the intense shame they suffer.

"I don’t expect anyone to be sympathetic to those who reap high rewards and prestige for their deception, but it bears remembering that they do pay a psychological price," Tansey says. "For a high-profile person like Lance Armstrong to maintain his lie requires an inordinate amount of energy. Most people don’t live in that space well. The pain is significant."

To get to this place, Tansey says a person experiences a breakdown in ethical reasoning—the ability to discern the right priorities from a host of values. Even when athletes know what they should do, their judgment becomes clouded by excuses, justifications, and desperate desire. To rationalize and cope with their faulty decisions, they can deceive themselves or engage in an unconscious defense mechanism called compartmentalization in which they psychologically separate the poor choice from the rest of their personal values and behavior. While egotistical self-interest fuels such decision-making, Tansey also agrees with Gaffney that current culture makes it easy to select bad choices.

"When we hero worship and give an inordinate amount of money to people who win, there’s a dissonance between what we say is the highest value and what we demonstrate in our behaviors," Tansey says. "Many athletes recognize this and act on what society does, not what it says."

“It’s funny how humans have this internal conflict. Our nature wants to believe athletes–and we do as long as they’re hiding the truth. When we find out, we’re really upset.” Ned Amendola

In extreme cases, cheating becomes a political or lucrative business enterprise. Gaffney recalls East Germany’s sophisticated master plan to achieve worldwide notoriety through its women’s swimming team in the 1976 Montreal Olympics. The conspiracy included doping the swimmers with steroids—instructing "The Wonder Girls" to "take their vitamins"—developing a world-class testing lab, and honing the regimen so that the athletes would continue to pass drug tests. With muscles upon muscles, these women crushed the competition, winning 11 out of 13 gold medals. Later, several reported enlarged hearts, gynecological problems, and birth defects in their children. Some eventually took their own lives.

In the U.S., "BALCO" reigns as one of the more high-profile debacles of recent years. Barry Bonds and Marion Jones were two of the more well-known figures in the Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative (BALCO) scandal, which ended in a 2003 federal investigation of owner Victor Conte’s business. Marketed as a company specializing in blood and urine assessment and food supplements, BALCO secretly distributed performance-enhancing drugs to MLB players and Olympians for many years. The company’s chemists developed "designer steroids" undetectable by current drug tests, including one aptly named "The Clear." Conte served a few months in prison for his role and, although BALCO is no more, he now runs a new sports nutrition business.

Recently, other ventures known as "anti-aging" clinics have been accused of peddling enhancers to pro athletes on the side. Even legal drugs can be used for illegal ends; new pharmaceuticals being developed for actual medical conditions like muscular dystrophy could eventually end up in the wrong hands. In the world of professional athletes and Olympians, it’s easier to find coaches and trainers willing to help obtain designer drugs or dodge the testing system by administering "microdoses" of enhancers that metabolize quickly and leave no lasting trace. At the university level, however, sports are more stringently controlled.

With a multidisciplinary team, the UI Sports Medicine Clinic provides a full spectrum of treatment and rehabilitation services for athletic injuries and sports-related medical problems. Here, patients receive a comprehensive approach to all their needs, including optimal injury management, nutritional advice, and psychosocial support. Sometimes, the clinic’s medical staff provides counseling to athletes who test positive for a banned substance, whether a performance enhancer or an illegal drug such as marijuana or cocaine. Of the some 900 tests conducted each year on Hawkeye athletes, less than one percent returns a positive result.

UI psychiatry professor Del Miller, 77BSPh, 91R, 92F, directs the drug testing program for Iowa’s athletic department, partnering with an external company to ensure objectivity. The in-house program conducts random urine testing on student-athletes throughout the year, aiming to screen everyone at least once. In addition, Hawkeyes must undergo random drug testing by both the Big Ten conference and the NCAA.

If a test comes back positive, Miller investigates. In the case of a prescription medication like Adderall or a narcotic, his research ends if the athlete has a doctor’s prescription on medical record. Without a legitimate diagnosis for their drug use, athletes face consequences that include community service, suspension, and possible expulsion from the program.

"We don’t exist to be punitive; one of our most important goals is to educate our athletes about the risks and dangers," says Miller, stressing the program’s counseling and treatment aspects. While he believes doping is a bigger problem at sports’ higher levels, Miller admits it would be naïve to believe that some athletes don’t slip through the cracks of collegiate testing programs. "Still, I’m impressed with Iowa’s coaching staff," he says. "I really believe they’re trying hard to provide good direction."

Iowa coaches believe strongly in those traditional sports values that emphasize character, respect, and tenacity. But what about the rest of the world—all the other coaches, athletes, and fans? As better and more sophisticated drugs appear, what will the future of sport look like?

One theory suggests accepting the situation, giving up the fight against drug use, and dividing competitions into camps of "enhanced" and "natural." Body- building—a sport constantly dogged by rumors of steroid use to produce inhuman amounts of muscle— already takes this approach. Gaffney despairs of such a sell-out. To legalize cheating, he says, shows a real disregard for the dangers of PEDS. Ultimately, he believes true change will only come with a major crackdown on top managers who know what’s going on but choose to ignore or enable the problem for their team’s benefit and financial gain. In one positive step, the NFL hopes to start blood testing players for human growth hormone next season.

Courageous action by sports leaders to remove incentives and deter drug use sets a good example for a clean environment. In addition, fans can do their part by throwing support and ticket sales behind the people who play fair, while athletes can just say no to illegal performance-enhancers.

In her retirement speech earlier this year, Welsh Olympic gold medalist and professional road race champion Nicole Cook spoke about her personal choice to ride clean. With words both inspiring and scathing, Cooke revealed the intense pressure her profession placed on her to dope, but she adamantly resisted— and still managed to emerge a decorated leader among female cyclists. She loved her sport too much to compromise its integrity.

"I am appalled that so many [athletes] bleat on about the fact that the pressures were too great," Cooke said. "Too great for what? This is not doing 71 mph on the motorway when the legal limit is 70. This is stealing somebody else’s livelihood. It is theft just as much as putting your hand in a purse or wallet and taking money. Theft has gone on since the dawn of time but because somebody, somewhere else does it does not mean it’s right for you to do it. There can be no excuse."

Dubbed the Anti-Lance Armstrong by the media, Cooke fears that her sport will never clean up when the rewards of "stealing" are greater than the alternative. And, for all the front-page scandals about disgraced athletes, people like Armstrong—who finally get caught in their lies—are a minority compared to the countless other athletes who evade detection. Still, a common denominator exists in these stories of fallen stars: they didn’t get away with it. The trophies they won eventually went to the guy in second place.

In the words of author Edgar J. Mohn: "A lie has speed, but the truth has endurance."

Will truth win in the end?