Latinos have been living in and shaping the Midwest for generations, yet they rarely appear in historic accounts. University of Iowa faculty and staff are working to set the record straight.

Throughout the entire semester, as Omar Valerio-Jiménez taught a UI class on Mexican-American history, one shy young female student didn't utter a word. Then, inspired one day by the unexpected sight of a familiar face in a slide presentation, she finally broke her silence.

"That woman, that woman there," she said. "That's my grandmother."

The time-worn image of a Hispanic woman in Iowa, along with the student's surprise at seeing her relative, perfectly captured a theme of Valerio-Jiménez's course: Latino immigrants are a long-standing—yet often invisible—part of Iowa history.

In fact, when Valerio-Jiménez, an associate professor of history in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, joined the UI in 2006, even some of his colleagues in academia asked, "Are there Latinos in Iowa?"

ALL HISTORIC PHOTOS AND DOCUMENTS COURTESY OF THE IOWA WOMEN'S ARCHIVES

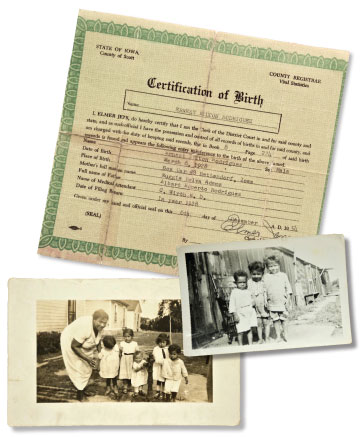

In the 1920s, many Latinos in Iowa lived in separate ethnic enclaves within existing towns. Muggie Adams Rodriguez, pictured with her daughter and neighborhood children in the photo at left, lived with her family in Holy City, a primarily Mexican settlement on the riverfront in Bettendorf. One of her sons, Ernest Rodriguez,

grew up to be a prominent civil rights leader in Iowa. His official birth certificate, seen above, notes that he was born in

"Box Car #8 Bettendorf, Iowa"

ALL HISTORIC PHOTOS AND DOCUMENTS COURTESY OF THE IOWA WOMEN'S ARCHIVES

In the 1920s, many Latinos in Iowa lived in separate ethnic enclaves within existing towns. Muggie Adams Rodriguez, pictured with her daughter and neighborhood children in the photo at left, lived with her family in Holy City, a primarily Mexican settlement on the riverfront in Bettendorf. One of her sons, Ernest Rodriguez,

grew up to be a prominent civil rights leader in Iowa. His official birth certificate, seen above, notes that he was born in

"Box Car #8 Bettendorf, Iowa"Actually, Latinos have lived and worked here since the 19th century, helping shape the state's economy, culture, and communities. Today, with their numbers fast increasing in both Iowa and the nation, their impact is more important and visible than ever before. In the words of a report from the recent White House Hispanic Community Action Summits, "Given the role that Hispanics will increasingly play in our labor force, in our economy, and in our public education system, it is undeniable that the success of our nation is inextricably tied to the success of the Hispanic community."

Yet, widespread, misleading, and damaging stereotypes often cast all Latinos as recent arrivals: uneducated, poor, working menial jobs, and undocumented. As revealed by recent research and scholarship, including groundbreaking new work from UI faculty and staff, the facts prove more complex and nuanced. In order for the U.S. to move into a future increasingly influenced by former minority groups, scholars like Valerio-Jiménez say we need to first understand and appreciate the past.

"As the public learns more, misunderstandings and fears about the impact of Latinos on local communities will lessen, and greater understanding will lead to greater appreciation," he says. "Increased knowledge will lead to better interethnic relations."

Nationally, Hispanics comprise the largest and fastest-growing segment of the population, with the recent census tagging them as more than 54 million strong. As such, they're an emerging economic, cultural, and political force. In the Midwest, Latinos represent the largest minority group, accounting for 7 percent across the region and 5 percent in Iowa. Significantly, they're the largest and fastest-growing ethnic minority in Iowa's public schools, with the number of Latino students increasing from 1985 to 2005 by almost 600 percent—to some 41,000 students or 8 percent of the total K-12 population.

At the college level, the number of 18- to 24 year-old Latinos enrolled nationally surged 24 percent in 2010, to hit a high of 1.8 million students. At the UI, Latinos are the largest minority student group; from 2010 to 2012, their numbers increased by 37 percent (1,099 to 1,505 students) to claim 4.8 percent of total enrollment. For these reasons, the university has expanded its outreach to Latino prospective students, hired faculty members with expertise in related issues, and supported a growing body of research on Latinos.

PHOTO: MATTHEW BUTLER/UI LIBRARIES

"Far from newcomers, many of Iowa's Latinos proudly claim multigenerational histories in the U.S. Here, at a 2012 Iowa Women's Archives' exhibit at the UI Libraries, UI student Nicole Vrankin stands with her mother, Patricia Vrankin, and grandmother, Florence Vallejo Terronez, beneath a photograph of her great-grandmother, Martina Morado, who came to the U.S. from Mexico in 1910.

PHOTO: MATTHEW BUTLER/UI LIBRARIES

"Far from newcomers, many of Iowa's Latinos proudly claim multigenerational histories in the U.S. Here, at a 2012 Iowa Women's Archives' exhibit at the UI Libraries, UI student Nicole Vrankin stands with her mother, Patricia Vrankin, and grandmother, Florence Vallejo Terronez, beneath a photograph of her great-grandmother, Martina Morado, who came to the U.S. from Mexico in 1910.

Last fall, Valerio-Jiménez collaborated with two other UI Obermann Center for Advanced Studies fellows to host a symposium to provide critical facts and perspectives on this cultural phenomenon. "The Latino Midwest" brought scholars, artists, and musicians to the UI campus to showcase the history, education, politics, and culture of the predominant ethnic group in America's heartland. Related events included literary readings, art exhibits, performances, film screenings, and panel discussions.

The conference drew heavily on the work of the Iowa Women's Archives, which has been collecting documents related to Latinos in the Midwest since 2004. An accompanying exhibit showcased items from the archives' groundbreaking Mujeres Latinas Project, the first statewide collection of Latino documents, photos, and oral histories in Iowa, and one of only a few in the Midwest. Archives staff are still actively soliciting materials through the project, as well as brainstorming new ways to involve Latino communities in preserving their history.

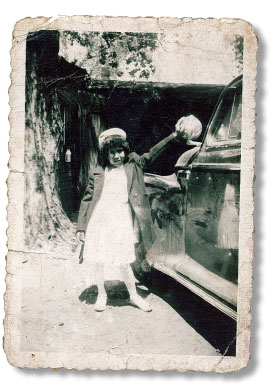

Maria Mercedes "Mercy" Aguilera is pictured on the day of her first communion in Davenport, 1948. A factory worker who was among the first Latinas hired to work at the International Harvester Company Farmall plant in Rock Island, Aguilera donated personal papers spanning 54 years to the Iowa Women's Archives' Mujeres Latinas Project. In 2005, she also recorded an oral history interview that can be heard at http://tinyurl.com/auwpkpt.

Maria Mercedes "Mercy" Aguilera is pictured on the day of her first communion in Davenport, 1948. A factory worker who was among the first Latinas hired to work at the International Harvester Company Farmall plant in Rock Island, Aguilera donated personal papers spanning 54 years to the Iowa Women's Archives' Mujeres Latinas Project. In 2005, she also recorded an oral history interview that can be heard at http://tinyurl.com/auwpkpt.The archives' rich resources help show that, ever since the 1880s, Latinos have made their way to the Midwest for all the reasons immigrants from every corner of the world have done: for a fresh start, better prospects, a chance to improve their lives. While many have worked in Iowa's fields and factories, on the railroads and in restaurants, educated professionals such as entrepreneurs, lawyers, artists, and academics have also contributed to the region's progress.

From the beginning, Latinos often encountered suspicion and hostility in their adopted communities—homogenous rural towns strongly influenced by the German, Dutch, Czech, and other European immigrants who had set roots there earlier. During tough economic times, some native Iowans grew doubly suspicious of the newcomers frequently recruited to work low-paying jobs in meatpacking and other manufacturing plants. Some felt as if their towns had been invaded—conquered, overrun by "foreigners" whose language, customs, and culture were unfamiliar.

Sandra Sánchez encountered such reactions in 1991 when she moved from Mexico to Iowa's capital. Even now, she vividly remembers walking her 7-year-old son to his classroom on the first day of school. As they passed another young student, the boy yelled out angrily.

"I didn't know English at the time—maybe five words—but I could hear the hate in his voice," Sánchez says. She asked the bilingual aide what the boy had shouted. "She told me he said, 'You dumb Mexicans. I am going to ask my dad for his rifle and I'm going to kill you.'"

Today, Sánchez still often encounters anger as she champions causes like immigration reform through her work as director of the American Friends Service Committee's Immigrants Voice Program, a Quaker-based organization for peace and justice in Des Moines. Yet, the last few decades have also produced positive changes.

About 15 miles outside Iowa City, a self-described "progressive" community embodies cultural infusion in action. In 2011, West Liberty became Iowa's first town with a Latino majority: 52 percent of the 3,700 residents, up from 40 percent in 2000. Although some are from Central America and the Caribbean, most of these Latinos are from Mexico.

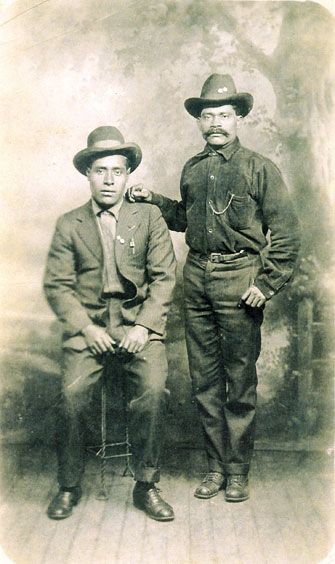

Two Hispanic men, probably dressed in their finest outfits for this special occasion, pose for a portrait in Bettendorf in the

1920s.

Two Hispanic men, probably dressed in their finest outfits for this special occasion, pose for a portrait in Bettendorf in the

1920s. West Liberty, which bills itself as "a community of opportunity," shows how vibrant Latino music and art can enliven a town; how Mexican food can spice up jaded U.S. palates; how immigrants can bring original ideas and perspectives—plus, on a more practical level, vital economic revitalization. In an interview last year with National Public Radio, Mayor Chad Thomas estimated that Hispanics own about half the businesses in West Liberty's thriving downtown. "[Without] the Hispanic population here," he told NPR, "... there would be a lot more [empty] store fronts."

The community also tackles the controversial issue of Spanish as a dominant language. In 1997, the West Liberty school district launched a dual-language program with a five-year, $1.7 million grant from the federal Department of Education. Critics of such initiatives object to limited government funds being directed to dual language programs or providing Spanish translations of official documents. Others insist that Latinos, like other immigrant groups before them, should adjust to mainstream America and learn English.

Yet, studies have shown that bilingual children benefit from greater cognitive development, increased listening skills and memory, and a greater understanding of their native language. West Liberty's emphasis on dual languages also provides students with a competitive edge in a global marketplace and prepares them to become leaders in Iowa's increasingly diverse cities and towns.

In fact, the voluntary program aims to develop kids who are not only bilingual, but bicultural—who understand and appreciate each other's history and cultures. This small Iowa town has embraced diversity in other ways, too, with some immigrant traditions literally becoming sources of celebration. Every year, people from all backgrounds visit the town to enjoy ethnic entertainment and food at events like the Latino Festival and the traditional Mexican feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

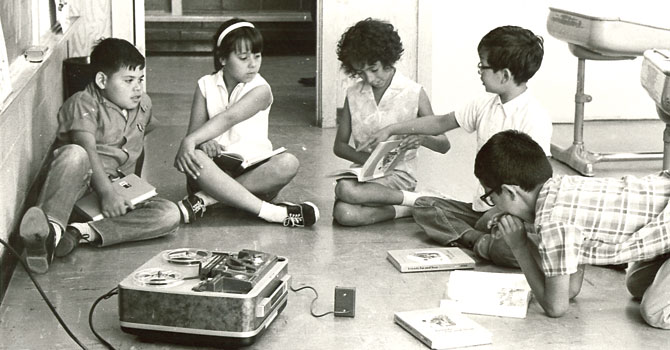

This photograph taken in Mason City, Iowa, in the 1960s, shows young children attending a school summer camp organized by the nonprofit Migrant Action Program, which provided educational and social services for seasonal agricultural laborers.

This photograph taken in Mason City, Iowa, in the 1960s, shows young children attending a school summer camp organized by the nonprofit Migrant Action Program, which provided educational and social services for seasonal agricultural laborers.

Growing up in Texas and spending many summers with relatives in Mexico, Valerio-Jiménez enjoyed such a bilingual and bicultural environment. But even Texas high schools didn't acknowledge the contributions of Latinos. Only after he enrolled at MIT for a joint bachelor's degree in engineering and humanities did Valerio-Jiménez complete other courses that helped fill the gap.

"As I took courses in Spanish literature, Mexican history, and U.S. politics, I realized that I had received a very politically conservative education in high school," he says. "I was fascinated and surprised to find that I hadn't learned previously about the history of Mexican-Americans or any other ethnic minorities."

Now, at the UI, Valerio-Jiménez is working to ensure that future generations of scholars receive a more inclusive education. Soon, he'll help present an Obermann Summer Seminar on "Teaching the Latino Midwest" that will bring educators to Iowa City for a week-long event to determine the direction of future educational efforts. Eventually, what's discussed there will be published as The Latino Midwest Reader, an anthology designed to be used in university and high school classrooms.

Finally, Iowa's Latinos will make it into the history books.

For more information about the Iowa Women's Archives and its Mujeres Latinas Project, visit www.lib.uiowa.edu/iwa/mujeres.