The story of a life unfurls from a handful of extraordinary days, those defining moments in time that underscore the whole beautiful mess.

A birthday, a first day of school, the day a heart breaks. A graduation day, a wedding day, the day a child is born. Each turning point deepens the story, adds a new plot twist, and brings with it love, loss, joy, and despair—most of the memories retold with remember that day when.

Julie Malott Knight was only 10 years old in 1970 when one of those days came along. She sat crinkling the paper cover on an exam table in an Ottumwa doctor's office, clutching an information pamphlet about diabetes and using a fifth-grader's logic to try to process a mountain of fear.

Average life expectancy: 18 years. The bold-lettered words trembled in Julie's hands and she hid the pamphlet in her book bag. She didn't want her parents to know she might not live past 30. But, of course, they knew the statistics. Her mother was a nurse, and then there was Virgil, her older brother diagnosed with diabetes when he was only three.

Says Julie: "I knew my life was about to change forever."

The number 30 seared on her brain, Julie Knight accepted she'd be lucky to live that long. Thirty became a dark cloud, an imaginary ending point that kept mortality ever-present in her young mind. She adopted the lifestyle adjustments that this chronic illness demands, taking insulin and a tin of sugar cubes to school in case her glucose levels went wonky. Like anyone, she had moments of weakness that occasionally involved a Peanut Buster Bar from the DQ. But she did her best, following the latest in diabetes control as the years rolled along.

Thirty came and went. So did 40. Julie Knight turned 50 last September, and, right before her birthday, she and husband Dan Knight, 97BLS, spoke at the international convention of the Fraternal Order of Eagles. She was there to applaud and reinforce the Eagles' commitment to diabetes research, in particular the organization's $25 million commitment to the University of Iowa.

PHOTO: MERCY IOWA CITY

PHOTO: MERCY IOWA CITYIn 2008, the Eagles announced their intent to fund a new Diabetes Research Center within the UI's Institute for Biomedical Discovery, under construction now on the medical campus. The gift—the single largest in the 114-year Eagle history—will support endowed chairs and fellowships for diabetes researchers, provide seed research grants for promising ideas, and help recruit leading scientists who can identify better prevention and treatment strategies. Ultimately, it will enable people like Julie Knight to live longer, healthier lives. Perhaps, one day, a life free from diabetes.

An estimated 26 million Americans have diabetes, according to the World Health Organization. That's approximately twice the number of people with cancer. Diabetes is also the most expensive chronic healthcare problem in the U.S. today, with billions of dollars going toward caring for people with the disease. Twenty years ago, diabetes affected seven million people, and the current growth reflects a true rise in prevalence—not just better screening and diagnosis. An increase in obesity, one of the prime risk factors for Type II diabetes, accounts for only part of the increase; much about the disease remains a mystery, which is why research is so crucial.

"We really need to get a hold on this or it's going to consume us," cautions John Stokes, UI professor of internal medicine and director of the UI Division of Nephrology, where he treats many patients in diabetes-induced kidney failure. "It's a serious epidemic, no question. You get a room full of people and practically everyone knows someone who's dealing with diabetes."

This is especially true in a room full of Eagles members, who know quite well the personal consequences of diabetes; some 30 percent of the organization's one-million-strong membership has the disorder. In 2006, Stokes—who joined the Eagles 20 years ago—attended a state convention and spoke with then international president Bill Loffer, who shared his conviction that the group should pursue a center for diabetes research. He believed it should be in the centrally located Midwest and at an institution with existing resources. Stokes told him that the University of Iowa had plans for a first-class facility dedicated to biomedical research on diseases like diabetes, cancer, and Alzheimer's—not to mention dozens of brilliant and creative experts devoted to medicine's most pressing problems. The UI offered 20,000 square feet of space in the new building, which appealed to the Eagles because they wanted to spend all their money on science, not bricks and mortar.

After considering all the national options, the organization selected the UI as its best partner. The collaboration will enable the UI to expand on its current leadership in diabetes research and become a premiere center, among the best in the world.

"Tough problems like diabetes require a multidisciplinary approach by people who think about questions from different perspectives. That is what this center is designed to do," Stokes says. "Sometimes, discoveries come serendipitously; we never know where we might find the answers."

Last spring, the UI officially named the facility the Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center. The Eagles have made good on $15 million of their commitment, some of which already has been applied toward hiring new faculty and funding early research grants. Even though the building won't be completed until 2014, breakthroughs are under way.

Diabetes always has been part of Julie Knight's life, starting with Virgil. He was potty-trained and quite proud of his Big Boy status when suddenly he started wetting the bed. His appetite grew insatiable and his mother grew suspicious that something was wrong. Sure enough, she was right.

So, Julie knew to worry when she started spending more time in the bathroom and losing weight despite her constant hunger. One day, after washing down 10 Reuben sandwiches with a gallon of milk, Julie took one of her brother's "Clinitest" kits to check for sugar in her urine (finger-prick blood-glucose monitoring wouldn't become available until the late 1970s). She deposited a few drops in the test tube, added water, dropped the telltale tablet, and waited for the liquid to change color.

A few seconds later, she screamed. The water had turned burnt orange, indicating her urine contained the highest possible amount of sugar. Soon, she was at the doctor with that pamphlet in her hands and tears falling down her cheeks. Julie had Type I diabetes.

PHOTO: Scott Van Blarcom/ISTOCK.COM

PHOTO: Scott Van Blarcom/ISTOCK.COM The most devastating form of the disorder, Type I diabetes occurs when a person's body makes antibodies against beta cells in the pancreas, rendering them incapable of producing the insulin that regulates levels of blood glucose. It can occur at any age, but is most often diagnosed in children and young adults. In Type II, usually manifesting later in life, the pancreas makes plenty of insulin—but the body does not use it effectively (known as insulin resistance). Exactly how or why either type develops in a particular individual remains unknown, but science suggests a root cause of genetic predisposition and environment.

Seemingly innocuous, sugar is an important source of energy for the body. But it's also the sort of substance that demands moderation—too much or too little causes big trouble. High blood-sugar levels wreak physiological havoc, damaging the body's blood vessels to a degree that affects almost every organ in the body. Complications include blindness, heart disease, kidney disease, loss of lower extremities, and stroke.

To avoid such dire developments, a Type I patient must inject insulin up to four times per day, and even then blood sugar can be extremely difficult to control. Treatment for Type II typically begins with diet and exercise modifications; if that doesn't work, pharmaceuticals or insulin might become necessary. Often, treatment approaches lose effectiveness and must be changed as a person ages. Psychologically, not just physically, the permanence of diabetes is a huge burden, one that simply overwhelms some people. Like many other diabetics, despite his awareness of the risks, Virgil never took very good care of himself; he died at age 35 of a massive heart attack.

Every person reacts differently to diabetes, so some patients have better success than others, experience fewer health problems, and have greater life expectancy. But, as Dan Knight says, "The insidious part of this disease is you can do everything right and it will still get you."

Julie knows how frustrating this can be. She now wears an insulin pump, attached to her clothes' waistband, which delivers precise dosages throughout the day via a catheter inserted into her belly. She watches her food intake, exercises regularly, and always keeps an ear open for the alarm that beeps if she needs to adjust her insulin. Any number of factors—stress, illness, a menstrual cycle, a day she doesn't walk her dogs—can set off the alarm.

Despite her meticulous efforts to stay as healthy as possible, Julie bears scars that speak to the enormity of her illness. In 1990, blood vessels in her eyes exploded, and she went blind for nine months until she could have corrective surgery. Although her sight was restored, she still has tunnel vision. Around this same time, she endured a miscarriage because her body was too battered and weak to sustain a child. She wonders when poor circulation will force the amputation of her toes or if today will bring the last sunset she sees.

She willingly tells her story wherever she can, at Eagles conventions and in video promotions for UI specialists, in hopes others won't have to suffer this way.

Doctors don't like to talk in terms of cure, but they do want to help their patients live the best life they can. "Diabetes is deeply embedded in our genes, and we can't change that," says Daryl Granner*, 58BA, 62MS, 62MD, founding director of the UI's new Eagles center and previous director of a comprehensive diabetes facility at Vanderbilt University. "The best we can do is prevent, delay, and treat—significant steps can be made at any one of these stages, so that's what we're going to do."

In that spirit, four young UI investigators recently received $50,000 first-year grants from the Eagle gift to pursue a range of molecular and genetic studies—such as how metabolic factors in diabetic mothers might increase their children's susceptibility, and the role a poor diet plays in disease development. Recipient Anne Kwitek, 96PhD, UI associate professor of pharmacology, wants to better understand the complexity of the genetics that underlie diabetes, including how genes interact with the environment to trigger its onset. Her project is to place rats susceptible or resistant to obesity, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol on a high-fat diet to note metabolic differences and see if the animals develop diabetes. She will then use new sequencing technologies to determine what genes are induced or repressed after a high-fat diet in the genetically susceptible versus resistant rats.

"If we're able to make them diabetic," she explains, "we can pinpoint what genes are turned on or off in that process and target those pathways."

In another lab, Eagle-supported UI endocrinologist Chris Adams discovered that ursolic acid—a substance found in apple peel and the skins of other fruit—lowered fat, blood sugar, cholesterol, and triglycerides in mice. For his work, Adams, 99MD, 99PhD, was named the diabetes research center's first faculty scholar, and he'll receive $250,000 over the next five years to further probe ursolic acid's potential as a treatment.

The Eagles gift has enabled the UI to hire two new recruits so far and should allow Iowa to add 12 to 15 additional faculty members in the next several years. "We will ask, 'What's going to be the most important thing to study in the next 10 years and who is best to do that?'" says Granner. "We need people who are bold and ambitious, and [the new center] allows us to compete for the best and brightest young faculty across the country."

When Julie met Dan, she became completely dedicated to living as long as possible.

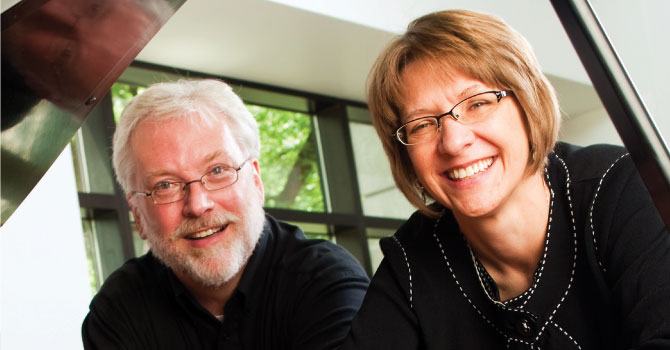

A renowned pianist and composer, Dan is a Steinway artist—one of only 1,800 in the world. He and Julie met in 1989 at a Von Maur department store, where he worked as the store's piano player and she in men's and women's clothing. A staff Trivial Pursuit party sparked their relationship—one that even diabetes couldn't destroy.

Diabetes never scared Dan—he knew it familiarly. His mother, who died from a stroke when he was only 16, used to suffer hypoglycemic attacks that left her catatonic, while his father died from Type II diabetes complications.

As for Julie, who'd determined that she'd live a lonely life until an early death, Dan was worth making herself vulnerable to hope. After Dan asked Julie to be his wife on their third date, they married in April 1990. "The only thing I was afraid of was missing out on the love of my life," Dan says.

Having lived with diabetes for 40 years, Julie is tough. But diabetes is greedy. She's optimistic about the possibilities at the University of Iowa, but that doesn't change the fact that her kidneys have begun to fail. She worries that sooner than later she will leave Dan all alone.

"We don't take the trash out without saying, 'I love you,'" Dan says.

Until then, they will eagerly await life-changing news from the University of Iowa—and a new day for people with diabetes.

Take Control

PHOTO: ROBYN MACKENZIE/ISTOCK.COM

PHOTO: ROBYN MACKENZIE/ISTOCK.COM

We all know the formula. A sensible diet + increased physical activity = healthy you.

The evidence keeps growing that this equation can prevent or delay the onset of Type II diabetes, perhaps eliminating the risk completely. Just last month, a University of Missouri study published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise showed that volunteers who decreased their daily activity experienced significant spikes in blood sugar after meals. Researchers could only conclude that prolonged inactivity creates physiologic conditions conducive to chronic diseases like diabetes.

Although the American Heart Association recommends that people take 10,000 steps or more—roughly five miles—per day, few Americans actually meet this goal. People aged over 45, with a family history of diabetes, who are overweight and do not exercise regularly, are at increased risk of developing Type II diabetes.

To reduce this risk, experts suggest people:

- Eat more whole grains, vegetables, and fruits and cut back on saturated fat and high-cholesterol foods. The American Diabetes Association endorses many cookbooks that can help you plan better meals.

- Exercise! You don't have to run ten miles a day to get fit. Pick an activity you like—whether walking, gardening, or yoga—and get moving. To really reduce your risk, aim for a minimum of 30 minutes five days per week.

- Enroll in a program like the University of Iowa's REACH (Reaching Euglycemia and Comprehensive Health). This eight-week lifestyle intervention course helps predisposed and pre-diabetic individuals make wise prevention choices.

For more tips like these from the American Diabetes Association, visit www.diabetes.org.