Jesse Albrecht's military uniform stood for respect. In basic training, he learned to rever every detail: its stitches and seams, its buttons and patches. He learned to fold each piece with precision.

The uniform stood for honor and history. Albrecht, 04MA, 06MFA, cherished the World War II dress uniform handed down by his grandfather. Other family members were veterans, too: his great-uncle survived the bombing at Pearl Harbor; another was shot in the legs during World War II; and two uncles serve in Vietnam.

The uniform stood for places and people: Mosul, Iraq, and Kuwait; fellow soldiers and ordinary Iraqi citizens.

Above: Former National Guard emergency medic Jesse Albrecht transforms his military uniform into art.

Above: Former National Guard emergency medic Jesse Albrecht transforms his military uniform into art.

"The uniform has a lot of weight attached to it," says Albrecht, who was an emergency medic with the Iowa Army National Guard, serving in Iraq from April 2003 to April 2004. "Even though each uniform looks the same, apart from its tags, it becomes your own. It becomes part of your identity."

But, his uniform also signified dark memories of war. It triggered memories of how he felt let down by the American government when he was sent to Iraq without bullet-blocking inserts for his body armor. It reminded him of the hardships he face returning home to a place where he often felt misunderstood.

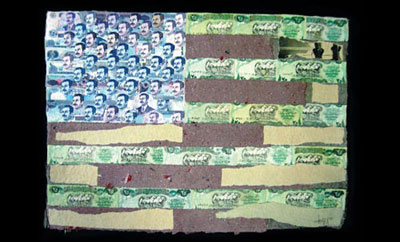

We Are All Free Now, 2008, by Drew Cameron. Iraq currency on combat paper with abaca.

We Are All Free Now, 2008, by Drew Cameron. Iraq currency on combat paper with abaca.

This past spring, for all these reasons—and many more that he can't express in words—Albrecht removed his military clothing from the Army green duffel bag tucked into the corner of his closet. He brought this physical reminder of his former life to the University of Iowa campus. Then. he carefully removed the buttons, cut his battle dress uniform into pieces, and beat it to a pulp.

He wasn't making a protest, though. Albrecht was making art.

Organized across the country and throughout the year by the Combat Paper Project, based in Burlington, Vermont, these workshops use the ancient art of papermaking to help vets reflect on their time in service and come to terms with their war experiences. They also aim to open up a conversation with local communities about the impact of war and Americans' responsibilities to veterans. With its internationally respected Center for the Book, expert staff, and unparalleled papermaking facilities, the UI was an ideal venue for this cathartic event.

Drew Cameron, co-founder of the Combat Paper Project, which uses art to help veterans share their experiences of war.

Drew Cameron, co-founder of the Combat Paper Project, which uses art to help veterans share their experiences of war.

At the UI, the ten-day artist-in-residency program included a studio tour, lecture, poetry reading, and open house. In addition to the free papermaking workshop, veterans could also participate in a writing workshop with Emma Rainey, 06BA, 09MFA, an alumna of the UI Nonfiction Writing Program who gre up in a military family.

The event was both out of the ordinary and yet also in step with the outreach mission of the UI Center for the Book, says Matt Brown, the center's director and an associate professor of English, who worked for more than four months to raise financial support to bring the papermakers to campus. In addition to the Center for the Book, Humanities Iowa and a number of UI departments co-sponsored the event.

"We saw this as a way to reach out to the veteran community," Brown says. "One of the really thrilling things was to hear testimony from the veterans about how working with their hands like this gave them a way to redefine the vet experience. It was potentially therapeutic, while the public events were a chance for them to discuss the meaning of their service."

A sacred act

On the surface, turning a military uniform into paper may seem like a disrespectful act.

But, hand papermaking is an ancient art, passed down from generation to generation for centuries. Throughout history, paper has carried our deepest emotions: through love letters, diaries, poetry, and painting.

"To make a piece of paper is a sacred act," says Tim Barrett, a MacArthur Genius Grant recipient, research scientist, and adjunct professor in the Center for the Book. "To make paper out of your uniform, to think about the stuff you had stored away with that uniform, it can be a very powerful experience."

As he discovered during the workshop, Barrett indirectly helped bring about the Combat Paper Project. He once taught papermaking to a young man who later handed down the craft to his son, Drew Cameron. In 2007, several years after serving as an Army artilleryman in Iraq, Cameron co-founded the project.

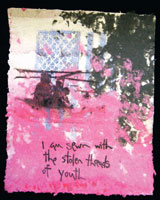

Stolen Youth, 2009, by Drew Cameron and Drew Matott. Pulp printing on combat paper.

Stolen Youth, 2009, by Drew Cameron and Drew Matott. Pulp printing on combat paper.

"I helped start the project as a reaction. I needed to express my experiences in the war to other people so they could understand what I'd been a part of," says Cameron, an Iowa City native. "When I was able to work in Iowa ten years after I'd enlisted, at the very studio that my knowledge of paper had initially derived from, with the same man who'd taught my father, it just seemed to come full circle."

In the last three years, the project has traveled across the country and to the United Kingdom and Canada, working with more than 120 veterans from every military branch and every modern major U.S. conflict—from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam to present-day service in Iraq. Vets can bring their own combat uniforms (which are their personal property, not the Pentagon's), but donated uniforms are also available to those who are either uncomfortable with cutting up their own or no longer have one.

Cameron acknowledges that destroying a uniform can stir up complicated emotions. Some vets tell him plainly that the act is wrong. Others are skeptical but open to the experience because they're looking for an outlet to share the memories stored away with their uniforms.

Specialist Collar, 2008, by John LaFalce. Combat paper sculpture.

Specialist Collar, 2008, by John LaFalce. Combat paper sculpture.

"Combat paper is made in honor of all men and women involved in war," explains the project's website. "It is created as a means of dealing with the experiences; it offers hope and support to those who are currently involved in combat, in offering that when they return home there is a vehicle for them to express their experiences and reclaim their lives."

In the workshops, veterans cut their uniforms into one-inch bits and then beat those into pulp by hand or machine to create an applesauce-like consistency. The slurry is then diluted with water and formed into sheets, which are pressed and dried. One 3.5-pound uniform—which may include a cap, socks, gloves, and undershirts—can make roughly 150 sheets of 8.5 by 11-inch paper.

Cameron takes a piece of each uniform from each workshop and adds it to the "lineage pulp" that goes into each new batch. "A little piece of each vet's uniform is in every new piece of paper made," he explains. "The project is collaborative in nature. We carry the strain in each sheet of paper."

During his career, the UI's Barrett has created exquisite handmade paper, including special sheets used to cushion and help preserve some of the nation's most treasured and significant documents: the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and the U.S Constitution.

He admits that paper made from uniforms alone is not necessarily high quality, "but that's not the point."

Airplanes, 2009, by John LaFalce. Pulp printing on combat paper.

Airplanes, 2009, by John LaFalce. Pulp printing on combat paper.

What's important is how participants use their combat paper. They create journals or books in which to record their innermost thoughts or painful memories. They transform the raw materials into glowing silkscreen prints or other pieces of art.

Just as wartime experiences are intensely personal, so are the works of art created during Combat Paper Project events. Some glorify militarism, while others overflow with anger. Guns, helicopters, slain comrades, blood, and graves present painful and often stark images. One veteran from the UI workshop depicted a rifle firing at an American flag.

In creating something new and beautiful from cloth tainted with painful memories, many vets find their emotional and psychological burdens lighten. With growing public and medical awareness of the mental toll of war, programs like the Combat Paper Project can provide a valuable therapeutic outlet. Whether called battle fatigue, shell shock, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), combat experiences can haunt and even wreck lives.

Still, it can be difficult to gauge the number of troops affected. The Department of Veterans Affairs' National Center for PTSD estimates that some 30 percent of Vietnam War veterans experienced such trauma, compared to about 12 percent of troops in the recent Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. Veterans groups and others insist that the numbers are far greater, especially as these modern conflicts expose service members to more violence and often require multiple tours of duty. Hundreds of thousands of former soldiers, they say, may be suffering from mental and emotional problems that affect their relationships, employment, and sense of self.

"The Combat Paper Project can become this really moving, personal experience that can be life-changing," Cameron says. "Many vets are in a place of despair, a place of darkness, and they use papermaking as a way to perform healing activities."

Stories within the fabric

As they toiled in the papermaking studio on the Oakdale Campus, a space secluded from the main UI areas, vets told stories and jokes. The sense of community and fun reminded Albrecht of the camaraderie he loved about the military. "Whenever you're with a group of people who share that experience, who understand all that crazy stuff you've been through, it takes the edge off," he says. "You don't have to worry about what other people think of you."

In that safe place, vets revealed the stories concealed within the fabric. When he returned home from Iraq, Albrecht was consumed with fear and emptiness. At

Chopper Landing, 2008, by Drew Cameron. Pulp printing on combat paper with kozo.

Chopper Landing, 2008, by Drew Cameron. Pulp printing on combat paper with kozo.

times, he carried a knife for protection. A professional sculptor whose work often includes military imagery, Albrecht used his workshop paper to create a sculpture of an M-16 rifle.

A symbol of modern Western warfare, the M-16 was a vital extension of Albrecht when he was a soldier. He slept inches away from it, carried it to the gym and to meals. "Then, when you're home and you don't have [your weapon], it creates a sense of panic," he says. "Most people look at it as an assault rifle, but I saw it as a lifeline. It became a symbol of how much I was changed by the experience."

Iowa City's literary legacy coupled with the UI's state-of-the-art papermaking resources produced "a phenomenally dynamic residency," Cameron says. "To have

access to a papermaking facility considered the best in the country and this amazing staff of practitioners, papermakers, and bookmakers helped us produce a significant body of work."

As the organizers hoped, veterans weren't the only ones to gain new insights. After a poetry reading, Barrett approached one of the ex-military papermakers, gave him a hug, and told him he was sorry for all that he'd been through.

"Our culture feels a deep obligation to service people," Barrett says. "Even if we don't believe in the war being fought, we feel indebted to them for their service. It's often hard to know what to do or to say. This opened up the door to that conversation."

For his part, Albrecht found the workshop experience so moving that he traveled to the East Coast with the Combat Paper Project this past summer to teach other vets the art of papermaking. "When you create an object, the experience isn't just bottled up inside you," he says. "You create something that's bigger than you, bigger than the experience."

Paradoxically, the fragile medium of paper proves strong enough to capture and transcend the horrors of war. Like the veterans who create it, combat paper offers a testament to the capacity of the human spirit to endure, to overcome, and—against all odds—to illuminate the darkness.