Thoughts explode, unfiltered and unrelenting, like fire inside his skull. He can't eat or sleep because they demand expression, so he writes and writes and writes to quiet them down.

When I see the flames coming, I try hard to stop them. I can smell them a mile away. They're always there burning, somewhere or another, consuming something every day.

His ideas explore the nature of reality and the core of existence—what is real and what is not. They lift him high, so high, until exhaustion takes hold. Just as wild waves on an ocean tide fade out to sea, the mania finally recedes. And he is left so low that getting out of bed in the morning becomes a philosophical and physical struggle.

Finally, it all becomes more than he can bear. But Brett Brinkmeyer does not pick up a gun or plan an act of mass violence—unlike troubled young men such as Jared Loughner, who captured national attention this past January when he opened fire outside an Arizona supermarket. Instead, in the bitter cold winter of early 2005, he walks through the door of his parents' home in Ames and utters the most courageous words of his life:

"I need help. I'm not sure for what, but I need help."These words propelled Brinkmeyer on a journey toward a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, a mental illness that swings between manic fits of elevated mood and major depression. Now aged 31 and an English junior at the University of Iowa, he controls the mind-clatter with a daily dose of the drug aripiprazole (marketed under the name Abilify) and regular visits with a psychiatrist. It was a harrowing effort, but Brinkmeyer found a way out of the darkness that threatened to destroy his sanity and his life.

College is a life-changing rite of passage into adulthood, a time of independence, self-discovery, and education. According to recent surveys and news reports, it's also a time when many young people wrestle with their inner demons—and a growing number of them join Brinkmeyer in the desire to overcome such psychological turmoil. With an estimated one in seven college students reporting difficulty functioning at school due to a mental health issue, campus counseling centers across the nation—including the UI's own University Counseling Service (UCS)—are stretching to accommodate a high demand for services.

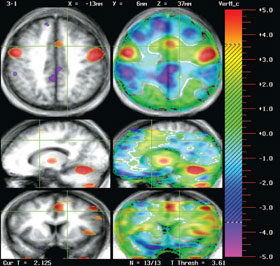

Advanced medical technology enables researchers to see the physical differences between the brain of a healthy person (left) and one with a mental disorder.

Advanced medical technology enables researchers to see the physical differences between the brain of a healthy person (left) and one with a mental disorder.These students need help not only for problems like academic stress, romantic heartbreak, employment worries, identity crises, and anxiety, but for more serious issues like depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. (A recent study by the American College Counseling Association concluded that 44 percent of students who seek campus counseling have severe psychiatric disorders, up 16 percent from ten years ago.) Previously, young people with serious mental health problems had no hope of functioning in a campus setting; today, improved medications have made a college career possible.

"What were the options 25 years ago? A halfway house or a state hospital," says UCS director Sam Cochran, whose center experienced an 11 percent increase in overall visits in 2009- 10 compared to the year before. "Now, we have better solutions—more young people are being identified and treated before they even get to campus. Thankfully, parents and their students also are more knowledgeable and have broken down some of the stigma associated with mental illness."

In other words, seeking help carries less shame. Unwilling to struggle alone in silence, today's college students realize they can get support to pursue their goals and make productive, meaningful contributions to society.

Still, it was difficult for Brinkmeyer to swallow his pride, overcome the stereotype that—particularly as a man—he should be able to control his "emotions," and finally put his life in someone else's hands. Even back in high school, a friend once told Brinkmeyer that his thoughts seemed more important than the people around him, an early clue that his mental state was askew. He'd long felt isolated and misunderstood—feelings that only grew stronger with each passing year.

"I always felt like I was in the wrong place at the wrong time," says Brinkmeyer, who really started to decline after graduating high school. "I was lonely, disconnected, displaced. Everyone around me seemed to have more answers."

Nancy Andreasen*, 70MD, the Andrew H. Woods chair of psychiatry in the UI Carver College of Medicine and a National Medal of Science winner for her pioneering work in brain imaging, points out that brain development reaches its peak during adolescence. A number of biological processes occur as the brain—with its stunning complexity of one billion nerve cells—grows into maturity to create a massive network of connections that unite our physical, mental, and emotional lives. Unfortunately, in some people some of these pathways just don't get built.

By the time he reached his early 20s, Brinkmeyer felt totally adrift and consumed by his as-yet-undiagnosed illness. In fact, three-quarters of all lifetime cases of mental illness begin by age 24. Experts say young adulthood is often a characteristic time for the onset of a severe issue, particularly schizophrenia and often, as in Brinkmeyer's case, bipolar disorder. Physiology can collide with environment—such as the tough transition of being at college, away from home—to trigger and exacerbate symptoms.

In any given year, statistics show that roughly ten to 12 percent of a university's student body will likely suffer from either a mood or anxiety disorder, which is why campus counseling centers serve an important purpose. Established by the G.I. bill in 1946 to assist veterans returning home from war, the UI's University Counseling Service soon expanded to take its place among the country's first full-service student counseling centers. Cochran estimates that some 4,000 UI students could probably benefit from personal counseling, yet the center's professionals (12 senior psychologists, three pre-doctoral psychology interns, and 15 doctoral trainees in counseling and clinical psychology) will probably see only half that number. He stresses that the free and confidential help UCS can provide does not require an extensive investment of time; students can benefit from just three to four counseling sessions (Brinkmeyer is not among the center's clients; he works with another psychiatrist elsewhere). Plus, they can also attend one of the multiple support groups that the center organizes.

In addition to these outlets, several dedicated individuals have reorganized the UI's local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). Since the first well-attended meeting in

February, NAMI leaders have watched their listserv members multiply in numbers. They are hopeful the group's presence will improve campus life for UI students, as well as increase awareness about mental illness.

Such positive strides on college campuses represent the good news. The bad news is that stereotypes about the mentally ill persist, and treatment remains elusive for many people. Some very sick individuals fly below the radar, or enter the mental healthcare system only to receive ineffective treatment that doesn't match the complexity of their illnesses. Others refuse treatment at all, taking advantage of laws that make it difficult (if not impossible) to get help for a person who does not want it. Worse, they may tragically take their own lives.

Many end up in homeless shelters or jails, as did Iowa's Mark Becker earlier this year after receiving a life sentence for fatally shooting beloved Aplington-Parkersburg football coach Ed Thomas in 2009. A paranoid schizophrenic, Becker told police he believed Thomas was a "devil tyrant." During his trial, attorneys debated whether he was sane at the time of the shooting. In a recent letter to the Iowa City Press-Citizen, Becker's mother, Joan, pleaded for lawmakers to address mental health treatment and reform. She wrote, "On April 18, 2009, I called our local county central point of coordination during a horrible psychotic episode my son was having. I asked the question, 'What is it going to take to get help for our son? What has to happen before someone will listen to us?' Everyone now knows the events of June 24, 2009."

Andreasen agrees that the healthcare system is flawed. "The whole system is a mess. Hospitals are understaffed; there is no longer any long-term care," she says. "Someone with mental illness is every bit as sick as someone with congestive heart failure or cancer. But partly because of stigma and partly because of economics, our treatment facilities remain woefully inadequate."

Andreasen's imaging work shows consistent and significant structural differences in the brains of healthy people versus those with a mental disorder. Patients with mental illnesses typically suffer a loss of tissue in the frontal and temporal lobes—areas critical to higher-order cognition and other important functions. Yet, judgment and misconception about the mentally ill gain new ground every time a rifletoting psychotic makes the evening news. Although the U.S. Surgeon General reports that you are about three times more likely to be struck by a lightning bolt than suffer violence at the hands of someone with psychiatric problems, the image of the homicidal maniac once again becomes the unfortunate poster child for mental disorders.

As he reads the latest headlines from Tucson—where 22-year-old Jared Loughner's psychotic rage prompted him to gun down 19 people, killing six and critically wounding a U.S. congresswoman—Brinkmeyer laments such responses. "People are afraid of what they don't understand," he says. "So it's easy to cluster them together—to associate mental illness with murder—and be afraid of them all."

Of course, the University of Iowa will never forget November 1, 1991, when physics and astronomy graduate student Gang Lu—infuriated that his dissertation did not win a coveted prize—killed three senior members of his department, a fellow graduate student, and the UI's associate vice president with a .38 caliber revolver. He also shot and critically injured a student worker before killing himself. After the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre, the deadliest shooting rampage in U.S. history, schools and universities nationwide hurried to improve campus safety measures. The UI allocated resources to hire an additional psychologist at University Counseling Service, established an official threat assessment team, and initiated the "Hawk Alert system," which uses phone calls, text messages, and e-mails to mass notify the entire campus community of threats to physical safety.

By all accounts, it appears administrators at Pima County Community College, where Loughner attended class, did what they could to protect the public. They reported warning flags about his unusual behavior, and he was even suspended from school with the recommendation to seek a mental health evaluation. He never got one.

While the loss of innocent life during such violent events is obviously tragic, Andreasen points out a greater tragedy: the staggering waste of human potential due to mental illness. A World Health Organization survey summarizing the global burden of disease ranks depression as the leading cause of years lost due to disability, with other kinds of brain disorders topping the list. In the U.S. alone, the cost of mental illness is estimated at $79 billion, most of it from lost productivity.

"These illnesses are prevalent, they produce a great deal of suffering, and many of them are very treatable," says Andreasen, adding that people with mental illness are still human beings and the boundary between "us and them" is blurrier than suggested in novels or films like One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

Brinkmeyer spent years in and out of psychiatric wards, enduring a diagnosis and treatment process that he calls dehumanizing, sterile, and traumatic—albeit necessary. He even escaped once, determined to head for Alaska, but only made it as far as the airport. He remembers the horrific times he faded in and out of consciousness as his doctors experimented with different drugs and doses to adjust his brain chemistry. He felt like a lab rat, behind bars in that part of the hospital where patients stay under lock and key. He practically suffocated under his own self-criticism and judgment, and he felt a horrible pit in his stomach when yet another psychiatrist assumed the hallmark look that all but screamed: I am talking to someone who is crazy.

"I am someone who is crazy," says Brinkmeyer, who, despite all this, knows he's one of the lucky ones who do receive treatment. "And that's a difficult realization. You question anything you've ever thought. I still ask myself, 'What's a normal brain? What is normal human experience? What is true and what is delusional?' I'm still working on the question of what is a good life and whether I can achieve it through treatment. I'm still working to accept myself."

The bonfire in Brinkmeyer's mind is now a flickering candle. He sometimes misses it, though. His medications can muffle his emotions and stifle his creativity. He ponders the mixed blessing and curse of living with mental illness, and he considers all the beautiful works and inventions attributed to history's mad poets and scientists. He still wants to be a writer, to tap into the flames that once made him feel passionate and prolific.

The trauma from his experiences lingers, but he celebrates the miracle that he is alive. He urges people in similar darkness to reach out for help, to refuse to let illness take control, and to realize that they are not alone. As he writes in one of his poems:

Welcome to the Neighborhood , come in, put up your feet. You've been afoot awhile and you must be tired, I'll fetch something to eat.

Red Flags

While many students can cope with the demands and stresses of the college experience, others find it completely overwhelming. Mental health professionals with the UI's University Counseling Service (UCS) say that these signs may indicate that a friend or loved one needs help to achieve emotional balance:

- Noticeable decline in school performance;

- Noticeable signs of depression (persistent sadness, suicidal thoughts, apathy, fatigue, tearfulness, changes in eating habits, distractibility, sudden weight loss or gain);

- Nervousness, agitation, irritability, aggressiveness, non-stop talking;

- Bizarre behavior or speech;

- Extreme or sudden dependency on family or friends;

- Marked change in personal hygiene;

- Talk of suicide, either directly or indirectly;

- Comments in letters or e-mails that arouse concern.

For more information about UCS, please visit www.uiowa.edu/ucs. For more information and support resources regarding mental illness, visit the National Alliance on Mental Illness website.