Grant Wood (American, 1892-1942)

Stone City, Iowa, 1930

oil on wood panel, 30 1/4 x 40 inches

Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE

Gift of the Art Institute of Omaha

© Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Grant Wood (American, 1892-1942)

Stone City, Iowa, 1930

oil on wood panel, 30 1/4 x 40 inches

Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE

Gift of the Art Institute of Omaha

© Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Stroll the UI campus today and you'll find little evidence that the artist who created one of the world's most recognizable paintings spent seven years on the faculty. There's no Grant Wood Hall.

No Grant Wood Building. No Grant Wood Centre. No Grant Wood Wing or Studio. No Grant Wood Park or Place or Square. Not even Grant Wood's Ghost.

No Grant Wood nothing.

The life of the man who painted the world-famous American Gothic is embraced by other Iowa communities: Anamosa, Wood's hometown and location of his Stone City artist's colony in the 1930s; Cedar Rapids, where Wood lived for most of his life, and where he painted many of his early well-known works; and Eldon, the location of the real-life American Gothic house, where Wood is a one-man economic development machine and Gothic-related tourism makes up a good chunk of the town's economy.

Wood's days at the UI, though, are largely ignored. Why that came to be is not easy to explain, a combination of academic squabbles, personality clashes, and the movement of art history that led to a general forgetting of his tenure at the UI after he died in 1942.

Oh, yeah, and there was the gay thing.

"There's this public image of Grant Wood as a folksy icon, a simple man who painted plain images while wearing overalls, but as a painter and as a person, he's so much more interesting than the public allows him to be," says R. Tripp Evans, a professor of art history at Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts. His new biography of Wood, Grant Wood: A Life, published last fall, closely examines Iowa's most famous artist and his tenure on the UI faculty.

Wood was already famous when he came to the university in 1934. American Gothic had made him a celebrity four years earlier, and he lectured around the world, sold paintings for huge sums, and was prominently featured in a Time magazine cover story on the Regionalism style.

He joined the faculty as the Iowa director of the Public Works of Art Project, a Depression-era relief program that gave artists a government paycheck and academic credit to create public art. Wood oversaw the creation of murals and other art installations at post offices around the state and at Iowa State University, painting many of them in a drained swimming pool on the UI campus.

His tenure, though, was not a smooth one. Even Wood's hiring was apparently accompanied by some degree of controversy, which is cryptically alluded to in a copy of part of a report archived in the UI Libraries' Special Collections. Joni Kinsey, a UI professor of art and art history, says the details of the controversy and the name of the writer(s) are only in the full version of the report, and the only copy is apparently in a time capsule that was placed in the cornerstone of the Art and Art History Building in 1934. Until the cornerstone is opened, Kinsey says, the controversy will remain cryptic and mysterious.

Not long after Wood arrived at Iowa, the art faculty became made up mostly of Modernists who took their cues from Impressionism and other European forms. They considered Wood little more than a decent cartoonist, his Regionalist style as reactionary (described by one as "communazi"), his training questionable, his education inadequate, and his teaching heavy-handed. He was also rich and famous, a big strike among many academics.

And there was the gay thing.

Wood had ongoing disputes with other art department faculty in subsequent years, especially those who openly disdained his interest in Regionalist issues. His own behavior often strained the relationship further. Evans says he was generally suspicious of theory and held the academy at a distance. He also enjoyed working with regular folk.

"He loved teaching and was attentive to his students, and many of his students said he was the best teacher they ever had," Evans says. "He held public clinics around Iowa City and he critiqued paintings that people brought to him, which his colleagues didn't understand. He loved working with people, but the department thought that was absurd."

And then there was his image, which only reinforced the belief among some that he was a backward hick. Although he spent years studying in Europe and worked in the Impressionist and other European styles, Wood used an intuitive sense of image management to present himself as a down-home Iowan, the farmer-painter and common man. He didn't actually start painting in his trademark overalls until 1925, and it wasn't until Gothic made him a star that he fully gave up European styles and mostly disowned his work in them.

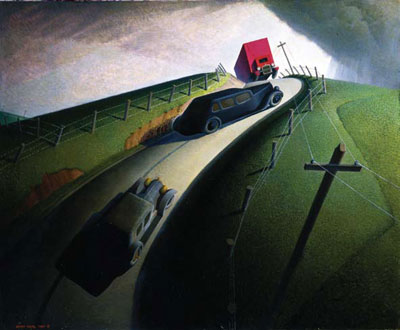

Grant Wood (American, 1892-1942)

Death on the Ridge Road, 1935

oil on masonite, 39 x 46 1/16 inches

Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, MA, Gift of Cole Porter

© Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Grant Wood (American, 1892-1942)

Death on the Ridge Road, 1935

oil on masonite, 39 x 46 1/16 inches

Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, MA, Gift of Cole Porter

© Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

"The idea is that he never fully embraced Impressionism and wasn't very good at it, but I think that's a myth," says Evans. "He was actually a very accomplished Impressionist. Maybe not distinguished, but accomplished. But after the success of American Gothic, he made the decision that this is the style he was going to work in."

Wood's time at the UI was artistically productive, as some of his most accomplished work—including Death on the Ridge Road and Parson Weems' Fable— was painted to acclaim while he was on the faculty. But that meant little to his detractors. If anything, it only gave another kick to the hornet's nest.

And there was still the gay thing.

By 1941, Wood's relationship with his colleagues had become so strained that some in the department moved to end it—and used his homosexuality against him. Evans says that many of Wood's friends in the art world and in Iowa City and Cedar Rapids suspected he was gay—especially after his mostly-for-show marriage ended in divorce in 1938 and he welcomed a number of handsome young roommates to his home at 1142 East Court Street. Other than a few whispers, though, people kept quiet about it.

His faculty opponents saw this as their ticket to get Wood off campus, so while he was away on sabbatical, they contacted a reporter from Time magazine. When the reporter showed up in November 1941 and started asking questions about Wood's "persuasion," President Virgil Hancher decided it was time to step in. Acting quickly, he managed to spike the Time story. Or perhaps the story spiked itself. The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor just a few weeks later, so Time's editors may have decided that reporting the sexual tendencies of a Midwestern artist was no longer the best use of their newsroom resources.

President Hancher also reorganized the art department to put Wood in a new division, apart from the mutual loathing society. After that, the outlook seemed to improve. Wood, who had fallen into a depression because of the ongoing departmental controversies and the risk to his reputation, perked up considerably. He looked forward to getting back in the classroom. Before he could resume teaching, though, Wood was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and his health deteriorated rapidly. He died February 12, 1942, at age 50.

Today, Wood is one of America's most acclaimed artists and American Gothic has been copied, imitated, and parodied so often that it's considered the second most recognizable painting in the world, behind only the Mona Lisa. Its home gallery is always crowded at the Art Institute of Chicago, and it draws huge audiences when it goes on the road.

All of which leads to the question, why is Wood still such a cipher on the UI campus?

"It's one of those things where it seems everybody knows about Grant Wood and the University of Iowa, except the University of Iowa," says Kinsey, who wrote about the artist's life and UI tenure as part of the exhibit book for the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art's Wood retrospective, "5 Turner Alley," in 2005.

Kinsey attributes part of it to an effort by Wood's detractors on the art faculty who were able to diminish his legacy once he was gone and would not let his spirit rest. "I think there was a concerted campaign to discredit Grant Wood and the whole Regionalist movement for years after his death," she says. "They really hated Wood, and made sure the university did nothing to remember him."

Evans agrees that Wood's tumultuous years on the faculty are a part of why he has so little presence at the university. He thinks it was also because of the stylistic direction that American art was taking. Regionalism was nearing its end in 1942 and would soon be replaced by Abstract Expressionism as the primary American artistic style. When that happened, Wood became an afterthought.

"The writing was on the wall for Wood and Regionalism when he died, so in the 1940s and 1950s, the university really had no reason to celebrate its connection to him," Evans says. By the time a Wood revival began in the 1970s, and places like Anamosa and Eldon embraced him as their own, the artist had largely disappeared from the university's institutional memory.

That conspicuous absence might be changing, as the university has recently taken several steps to reclaim its most famous art faculty member. The university's School of Art and Art History now hosts a biennial conference on Wood and his artistic impact, and there's discussion of remembering Wood in some way in a newly configured, post-flood arts campus. The university also has formed a partnership with Jim Hayes*, 64LLB, the current owner of Wood's Court Street house, to make it the centerpiece of a research center for Wood's legacy and Midwest art and culture.

"People look at his paintings and they see common people living simple lives, but many of those paintings have this power to unnerve us and we can't put our finger on why. That shows what a talented artist he was," says Evans. "I hope people come to realize that Grant Wood was everything they think he was—but a whole lot more."