A little-known UI athletic tradition may have been short-lived, but it was seriously good fun.

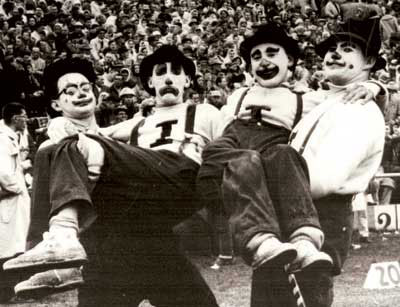

A frisson of nervous tension quivers through the locker room at Kinnick Stadium. It's the morning of an important football game, and a group of UI students gears up in preparation for the kick-off. They shrug into black pants and yellow sweatshirts adorned with a big block I. Then they reach for the most important items—black hats, butterfly nets, and face paint.

It's time to send in the clowns.

From 1957 to 1961, the University of Iowa—alone in the Big Ten and possibly the nation— boasted a clown squad. At a unique intersection where college football met rodeo, a small group of students entertained fans with comic antics and harmless pranks. The unlikely tradition began with a creative bunch of undergrads—and a kicker with a phenomenal right leg.

Back then, Kinnick Stadium bore little resemblance to its current state-of-the-art facilities. Instead of soaring brick walls, the stadium was partially enclosed by a chain-link fence; bleachers reached almost right down to the field, so spectators sat close to the action. Even the field goals lacked nets. As a result, talented kicker Bob Prescott, 61BBA, regularly sent footballs spinning far out into the stand, where souvenir-seeking fans eagerly snatched them up.

One night in spring 1957, over dinner at Hillcrest residence hall, three enterprising students—Bill Monson, Bob Burns, 58BSC, and Wayne Wessels, 58BSC—read a Daily Iowan article about the cost of all those lost footballs and came up with an innovative way to save the athletics department's budget. Led by Monson, a dramatic arts major who concocted the original idea, they approached athletics department staff, including Athletic Director Paul Brechler, 40MA, 43PhD [deceased], and suggested starting a small group of clowns to help retrieve footballs. Even though the students had no training or previous experience as clowns, the idea blossomed.

"It would probably never work now," admits Burns, referring to strict NCAA rules and the big-bucks television broadcasts that have made college football much more formal and business-like. "It was a whole different environment back then."

Indeed, it's hard to imagine a similar development today, with modern football fans accustomed to slick halftime routines, professionally choreographed entertainment, and instant video replays on the giant Jumbotron. Now, the concept of an amateur, unsupervised squad of entertainers seems endearingly quaint and innocent. Charles "Chick" Dykeman, 60BA, who joined the squad later in the fall of 1957, says simply, "We were the right people at the right time."

At first, Iowa Coach Forest Evashevski worried that the clowns would distract his players. Fortunately, Burns was a proctor (a precursor of a resident assistant) at Hillcrest and worked with many of the freshman players and their coach. So, Evashevski gave his approval, and members of the new squad took to the field that fall.

| Funny Guys |

After graduation, members of the original clown squad went their different ways and most lost touch. Then came a letter from former clown Ralph Hillman in the August 2009 issue of Iowa Alumni Magazine, asking whether anyone recalled this old Iowa tradition. "Remember? Sure do," former clown Ron Rogers wrote in reply. Soon, a few more clowns surfaced. Former squad member Charles "Chick" Dykeman*, 60BA, of Evergreen, Colorado, contacted the alumni association to help locate others. He managed to contact these eight other fellow clowns, all now retired from occupations that ranged from lawyer to medical researcher to university professor. None went on to a career in comedy. William "Bill" Bruns *, 65MD, of Omaha; Robert L. "Bob" Burns *, 58BSC, of Nisswa, Minnesota; Stewart Haylock *, 59BA, 61LLB, of Springfield, Ohio; Ralph E. Hillman *, 62BA, 65MA, of Murfreesboro, Tennessee; David S. Levinson, 61BA, 63LLB, of Seattle; Ron R. Rogers *, 61BSPE, of Tucson; Wayne Wessels *, 58BSC, of Granger, Indiana; Tom Wuerzberger *, 64BA, of Rancho Santa Margarita, California. Dykeman has been unable to make contact with only three of the original 12 clowns—Bill Monson, Marty Bassman, and Alan Bachrach. "We're all excited to have touched base with each other after 50 years," says Dykeman, who hopes to organize a clown reunion at this year's Homecoming. "Maybe this article will bring the others out of the woods." |

They bought their own uniforms—including baggy black pants with suspenders, white gloves, and black-and-gold striped canes—and they learned to apply make-up in the style of Depression-era circus clown Emmett Kelly.

Starting with the Utah State game in fall 1957 (which the Hawkeyes won 70-14), four clowns stood ready on the sidelines, prepared to amuse the crowds whenever action stalled on the gridiron. They brushed off officials' uniforms with whisk brooms and shined their shoes with towels. In the case of a disputed call, they pulled out a giant magnifying glass with which to examine the evidence. If members of the marching band dropped music sheets during the performance, the clowns rushed on field to retrieve them. During inclement weather, they acted as ball boys, carrying a supply of dry footballs under their shirts.

They also ran interference for Herky during lighthearted skirmishes with other schools' mascots. When dogs, squirrels, and rabbits strayed onto the field—a regular occurrence back then—the clowns scrambled in hot pursuit.

Their signature stunt involved attempting to snare wayward field goals in large butterfly nets, drawing great roars from the fans when they succeeded. "We were pretty good at it," recalls Burns. "We only lost two balls all season. Bob Prescott was an accurate kicker, so we always knew roughly where to stand."

Considering the clowns weren't jocks, they also executed some tough physical acts. They'd spring off a mini-trampoline or clamber up the field goal posts. Not content with attempting merely to walk the crossbar, they tried to traverse it on an old bicycle a couple of times. They were lucky to escape injury, although Burns does remember passing out near the 25-yard line in one game against Minnesota.

"Everyone ignored me because they thought I was just 'clowning around,'" he says. "Later that day, I went to student health services and was sent to the hospital. Turned out I had double pneumonia."

Given that the clowns performed in snow and rain, such hazards were to be expected. Nonetheless, they loved their work. "It was so much fun," says Dykeman. "At the time, I was working part-time at a funeral home in Iowa City. What we did on the field had nothing to do with our lives off the field."

The squad quickly became a popular part of Iowa game day tradition, along with the official Hawkeye marching band, the cheerleaders, and the famous Scottish Highlanders. Even at the height of their tomfoolery, the clowns were careful not to disrupt these other entertainers—or the football team. "The football players didn't interact with us," says Dykeman. "When they were on the field, they were so focused, they probably didn't even notice us."

At that time, Iowa enjoyed a national reputation for its athletic prowess. The Hawkeyes ended the 1957 season 7-1-1, were ranked sixth in the country by the Associated Press poll, and celebrated Alex Karras winning the coveted Outland award and placing second for the Heisman Trophy. A year later, Iowa claimed the Big Ten title, led the nation in offense, and topped a national football poll for the first time.

"Iowa played a brand of football like no one else. People who went to those games never forgot them," recalls Dykeman. "We got used to playing to full houses."

The clowns weren't involved for the glory, though—purely for the fun. Dykeman remembers that the UI athletics department would spring for gas money to away games but little else—after all, the clowns had originally pitched themselves as a money-saving measure. Still, they enjoyed the occasional perk—such as sharing the football team's locker room and listening in to some of Coach Evashevski's halftime pep talks, sprinkled liberally with his famously salty language.

"Coach would get the players so wound up," chuckles Dykeman. "You wouldn't want to get in their way going back down the tunnel."

During their tenure, the clowns appeared at every Iowa home game and several away games. They'd pile into Dykeman's automobile—a Ford Mainliner, not a clown car—and head off to Michigan State, Wisconsin, and other university towns across the Midwest, where they entertained crowds of up to 100,000 spectators. Back home in Iowa City, they occasionally appeared at Hawkeye basketball games, delighting fans with a Harlem Globetrotters-type routine.

Perhaps their most memorable performance came after the 1958 season, when the clowns joined the official athletic party that traveled by train to attend the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California. By any measure it was an unforgettable game: Coach Evashevski ignored his doctor's advice and rose from his sickbed to lead Iowa to a 38-12 victory over California; quarterback Randy Duncan* received a kiss from movie star Jayne Mansfield; and famed composer Meredith Willson led the Hawkeye marching band in a rendition of "The Iowa Fight Song," which he wrote in 1950.

For the clowns, the entire adventure—from start to finish—was a once-in-a-lifetime thrill.

"A couple of times a day there and back, we'd stop at a town, clamber off the Sante Fe train, and parade down Main Street with the band and the cheerleaders. The entire town would turn out to see us," recalls Dykeman, who was only 19 years old when he made it to the most famous college football post-season game. "We also appeared in the Rose Bowl parade, but there was so much pageantry we got lost in the shuffle. We didn't do our usual antics during the actual game, as we probably would've been thrown out of the stadium. Instead, we just wandered up and down the sidelines. We were a class act—like the football team and its fans."

Unlike the football team and its faithful followers, though, the clown squad proved short-lived. In 1961, after the original squad members graduated from the UI, some fraternities took over the tradition. Perhaps the squad outgrew the spirit of the times, but it gradually fizzled out. A few years later, Iowa's clowns hung up their butterfly nets for good.

Although most of today's fans are unaware that the squad ever existed, the clowns still vividly recall the smell of the greasepaint and the roar of the crowds. "It was one of those things you do and never regret," Burns says. "And you never forget, either."

For Iowa's inimitable clowns, there are no tears—only good memories and laughter.