The Well: An Iowa Med Student's Journey From Cancer Patient to Caregiver

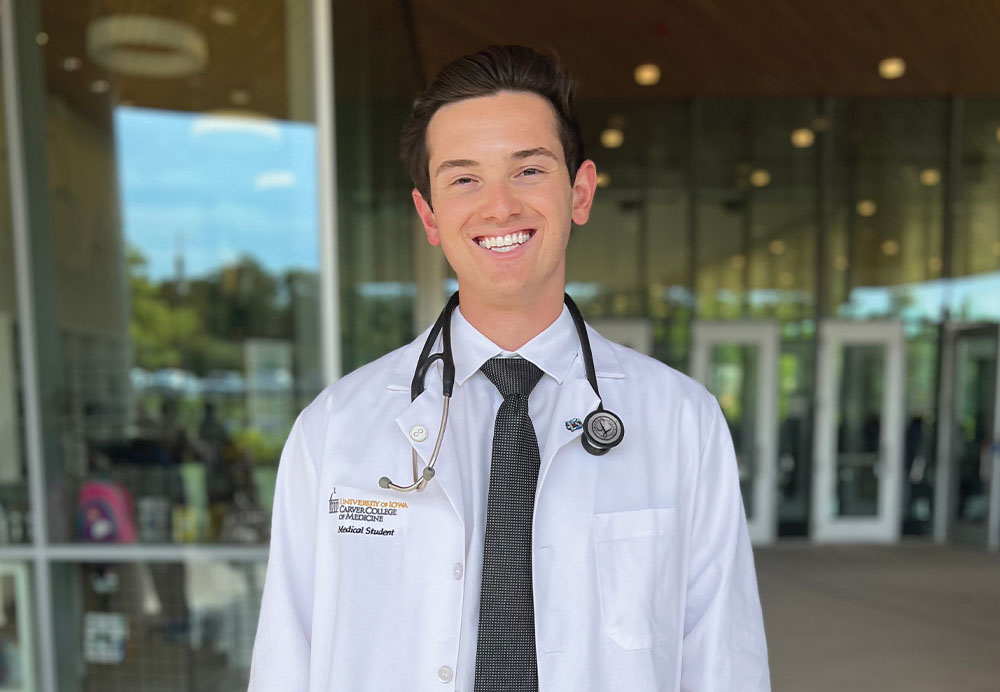

PHOTO COURTESY WILL MOODY

Carver College of Medicine student William Moody wears his white coat outside of Hancher Auditorium.

PHOTO COURTESY WILL MOODY

Carver College of Medicine student William Moody wears his white coat outside of Hancher Auditorium.

I could feel it seeping from my marrow and coagulating in my chest. The feeling rose like hot air. It became something more solid and intractable before the words burst out like an overfilled balloon.

“I had cancer too. I know what you’re going through, and I am so sorry,” I said.

The pressure dissipated, and I searched the patient’s face for a sign of recognition. A sign that they knew I was not another provider who nodded like they understood. Instead, a blank stare met me. A stare that said, “I am tired, and I have been tired for a long time.” I looked down, my cheeks reddening as the words I had spoken circled in my head. I thanked the patient for allowing me to see them. I gathered my notes and quietly shut the door as if that could somehow make up for the silence I had filled with my ignorance.

I had often visualized my first encounter with an oncology patient while I was going through chemotherapy. In my mind, we would build a rich and fulfilling interaction from a foundation of shared human experience. I had seen what I thought would be a beautiful moment of bonding between patient and caregiver. I imagined what it would be like when I was no longer the patient. I would no longer be the one afraid and unsure of the future. As a medical student with little experience in patient care, I built up that moment until it became something it could never be. Standing outside the room, left with a feeling of uncertainty, I wondered if I would ever be able to enter a patient’s room without the sense there was something I needed to say.

As I walked home, my mind wandered. I was brought back to a different room from some years ago that seemed too small to contain all the hopes of the men and women who passed through its door. I was seated in an exam room at my oncologist’s office. My hands nervously rubbed my legs while my palms soaked my pants with sweat. I had Hodgkin lymphoma. The disease had survived the initial onslaught of chemicals designed to eradicate every aberrant cell inside me.

At first, the cocktail had worked beautifully. A PET scan after four rounds of chemotherapy treatments showed that my cancer had retreated. My doctors told me I had more than a nine in 10 chance of being cured. I thought the additional eight grueling rounds I completed all but guaranteed success. Little did I realize that a small group of rebellious cells was biding its time.

My care was shifted to a more specialized facility, and I began salvage treatment. I always hated the term. The word seemed to indicate that my body was beyond repair and that I would be lucky if the scraps could be turned into something useful. My new oncologist was young and confident. She imbued in me her belief that, although my road ahead was difficult, it was nothing we could not handle. I began salvage therapy with a newfound resolve. However, the treatment carried only half the odds of success that the frontline therapy had promised. Seated in that room for my follow-up appointment, my life hung in the balance.

A resident I did not know entered and sat down facing the computer. He barely looked at me. He pulled up the scan I had thought about nonstop for the previous two months. I asked unsteadily if my cancer was gone, releasing my hopes and dreams, the same as many others had before me, like tossing a coin down a well.

“No,” he replied flatly.

His response was startlingly flippant, as though he thought I was naive for believing I could be free from cancer. He continued to speak, but I did not hear a word. He left the room, and my doctor entered. With a somber yet understanding look on her face, she told me about a newly approved medication. Although they were uncertain what the results would be, one thing was clear: My chances had steeply plummeted.

“How long can you keep me alive?” I asked.

My eyes welled with tears as she responded, “I had cancer too. I know what you’re going through, and I am so sorry.”

Her words let in a light where I had only seen darkness. In front of me was everything I wanted to become: a cancer survivor, a physician, and a person who deeply connected with those they encountered. Her disclosure moved me. The raw compassion was starkly juxtaposed with the distant behavior of the resident, and I knew I would strive to emulate her if I was ever able to become a doctor. I only saw her one more time, the day she told me I was cancer-free.

A few months after my encounter with the oncology patient, I began my neurology rotation. We had been warned that there was more morbidity and mortality on the service than many others. In the intervening months since I had seen the patient who sent me looking for an uncomfortable truth, I had grappled with how I wanted to respond to the next patient I would see. I did not have long before I was put to the test. A pager cut the silence in the team room. We were tasked with providing a prognosis for a patient. Her heart had stopped for many minutes before being resuscitated.

I knocked on the door of an ICU room and entered to three sets of eyes that threatened to pierce my veneer of calmness. After introducing myself, I began the physical exam. It was a choreographed yet desperate search for life. I shined my penlight into her eyes, trying to touch a soul attached to this Earth by a thread. I desperately wanted to convince myself there was a faint flicker of reaction. Instead, I wrote down “pupils bilaterally unreactive to light.” I moved through the rest of the exam. Each negative sign dealt a hammer blow to the dwindling hope on her daughter’s face. I turned to the family to ask if there was anything I could do to make them more comfortable, which they politely refused. I met each of their eyes, thanked them, and walked to the door. I felt a slight tug deep in my chest, but at that moment, I realized there was nothing more to say.

Later that day, I made the same journey home from the hospital I had all those months ago. As I reflected on the tragedy I had witnessed, I knew that I would never fully move on from my experiences as a cancer patient. However, with time, confidence would replace the uncertainty I felt. The truth I found following my initial encounter with the oncology patient was that there was no grandiosity in acceptance or a patient interaction so profound it justified my struggle. Acceptance was the quiet moment shared with a grieving family. It came softly on a walk in the fading hours of the day, not in a frantic moment of disclosure that was for no one’s benefit but my own. I used to feel the reason I was worthy to serve others was because I had overcome so much and that my patients would be able to benefit from my suffering. The trouble with that story was it left no room to let go. We are the stories that we tell, and sometimes, the most powerful are those that go untold.

COVER COURTESY THE EXAMINED LIFE JOURNAL

COVER COURTESY THE EXAMINED LIFE JOURNAL

William Moody is a third-year medical student at the University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine. This essay, originally titled “The Well,” placed second in the college’s Carol A. Bowman Creative Writing Contest, a competition established by Richard Caplan (51MA, 55MD) and sponsored by the college’s writing and humanities program. As a result, the piece was originally published in volume 12 of The Examined Life Journal, an annual literary publication of the Carver College of Medicine that explores the confluence of medicine and art. The journal can be purchased this fall online or at Prairie Lights or Sidekick Coffee & Books in Iowa City.