Behind the Plaster, an Iowa City Circus Mystery

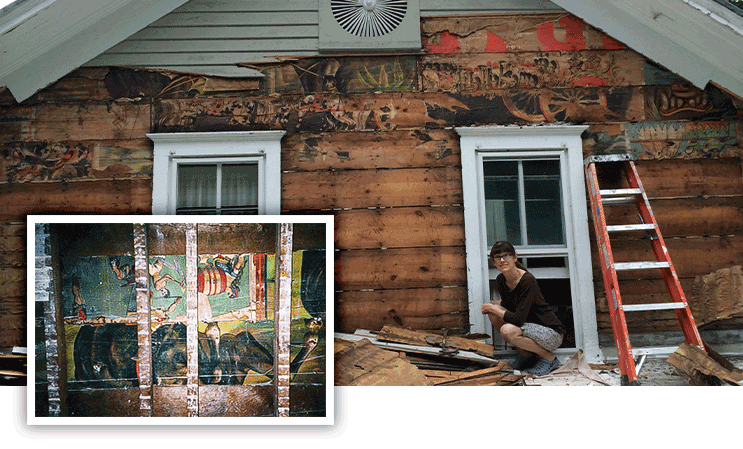

PHOTO COURTESY MARY HELEN STEFANIAK

Circus posters are discovered behind the walls and siding of Stefaniak’s home.

PHOTO COURTESY MARY HELEN STEFANIAK

Circus posters are discovered behind the walls and siding of Stefaniak’s home.

It’s hard to imagine how excited people must have been the first time the circus came to Iowa City. It was on a Monday in September, two days after the show in Des Moines. There must have been a crowd to meet the circus train, which was 50 railroad cars long. One hundred and seventeen horses! Twenty-five animal cages holding lions and tigers and at least one bear, plus a live hippopotamus! Whether P. T. Barnum called it his Great Traveling Exposition and World’s Fair or simply the Greatest Show on Earth, people must have lined up to watch the animals being led from the train. How many of them had ever seen an elephant or a camel before the circus came to town?

They must have been at least as astonished as my husband and I were in 2004 when, in the course of tearing out the walls of an upstairs bedroom in our former stagecoach inn, our daughter Liz spied the first signs of what lay hidden behind the plaster. “Come and see!” she called to me in the next bedroom. I squeezed through a pair of hand-hewn studs and soon we were wielding our crowbars side by side, exclaiming to one another in mask-muffled voices as chunks of plaster fell, revealing pictures of—what?

Was that a barrel? A horse’s—tail? The dust rose and then settled around us. Finally, we stepped back and took in what we had uncovered.

The entire wall of the bedroom—an exterior wall made up of 12-inch boards formerly covered by lath and plaster—was papered with circus posters.

They were in strips and pieces as wide as the boards they were pasted to, some words and images right side up, others upside down. Along with “The Greatest Show on Earth” and “Well worth going 100 miles to see,” we had uncovered the chests and pounding hooves of horses whose upper halves, we theorized, were on boards that faced the outside, under the clapboard siding. Balancing acts and trapeze artists appeared here and there. A woman in buttoned boots and a scandalously short skirt seemed to be lifting a barrel with her teeth. (This, we learned later, was “Millie DeGranville, the Woman with the Iron Jaw.”) In another picture, she lay back with an anvil resting on her midsection while a shirtless man with a handlebar mustache hoisted a sledgehammer over the anvil, as if in midstrike. (Apparently, she had an Iron Stomach too.)

In other rooms, we found lettering that spelled out “P. T. Barnum,” “Music Chariot,” and “Iowa City,” “Saturday,” “Sept. 8.” A poster fragment in the bathroom promised “A Stupendous Bear” and “The Only Living Hippopotamus” in America. In a corner of the master-bedroom-to-be, a pair of bare-breasted ladies posed demurely.

It was recycling, mid-19th-century style: a roadside barn or mill dismantled, the boards once papered to advertise the circus put into service a second time.

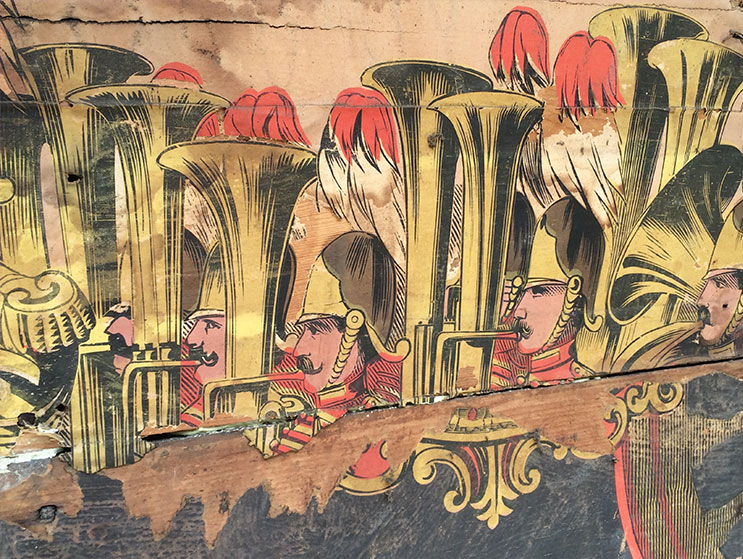

PHOTO COURTESY MARY HELEN STEFANIAK

A poster from Stefaniak's home depicts a marching band.

PHOTO COURTESY MARY HELEN STEFANIAK

A poster from Stefaniak's home depicts a marching band.

My first impulse was to call all our friends—maybe the local paper and the historical society too. Then I remembered the deadline on our construction loan. We had a lot more interior to demolish and haul away before our contractor could move on to plumbing, wiring, insulation, and the walls. We called just a few friends and took plenty of pictures. Then we covered all the poster-bearing walls with heavy-duty craft paper, ready for the insulation man.

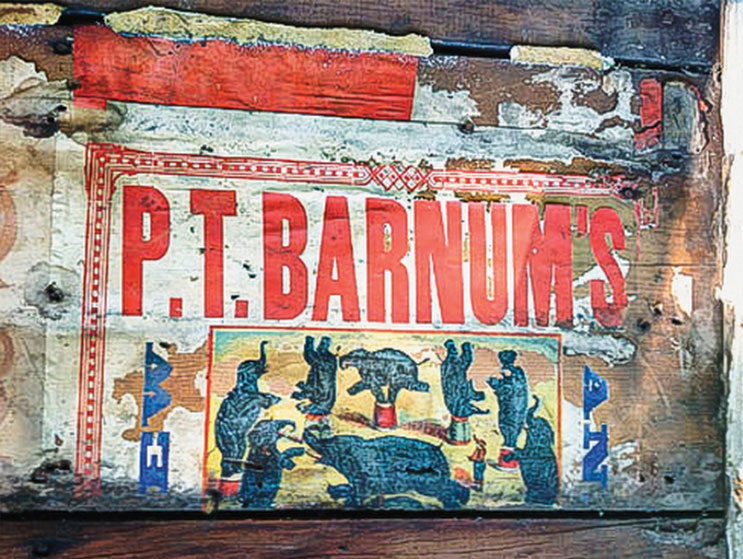

But we weren’t through with those circus posters. In summer 2007, we made a research stop at the Circus World Museum in Baraboo, Wisconsin. The librarian helped us hunt for a poster that matched the pieces we had discovered in our house. No luck there, but when it came to finding out what year Barnum played in Iowa City on “Saturday, Sept. 8,” all we had to do was look at a few early route books. Circuses kept daily journals that listed not only dates and places but how many miles were traveled, what the weather was like, and whether any mishaps occurred. We told the librarian that we would need to see route books from the mid-1850s.

Our house was widely believed to once be a stop on the Underground Railroad. In fact, I had recently read in Margaret N. Keyes’ Nineteenth Century Home Architecture of Iowa City that abolitionist John Brown might have once stopped at the inn. Local historian Irving Weber (1922BA) reported a construction date of 1857.

Suddenly, the librarian looked doubtful. “Well,” he said, “I can see a few problems there.”

The first problem was that Barnum didn’t take his circus on the road until 1871. The second was that Barnum didn’t even have a circus in 1857. The librarian believed that Barnum was still in New York City at that time, exhibiting Fiji mermaids at his American Museum. We turned to the route books. In 1871, Barnum and his circus hadn’t ventured any farther west than New York. In 1872, the circus had crossed the mighty Mississippi and played dozens of towns in Missouri, Iowa, and Kansas. The first show in Iowa City was on Monday, Sept. 9, 1872. The next was in August 1875.

We finally found “Saturday, Sept. 8” in the route book for 1877—more than a decade after the Civil War. A little late for the Underground Railroad. Maybe too late for a stagecoach stop.

We left the Circus World Museum feeling bereft. If part of the house was made of boards advertising a show in 1877, did that mean all the long-held lore about our home was incorrect? Were we living proof that, as Barnum reportedly said, “There’s a sucker born every minute”?

I guess nine years is as long as you can expect a feverishly scraped, hand-brushed exterior paint job on 150-year-old wooden siding to last. In summer 2013, nine years after we purchased our home, we decided to replace the old siding with “cement board”—long pre-primed boards that look like wooden clapboard made new. When we took the old siding off, we weren’t exactly surprised to find the sheathing underneath haphazardly plastered with strips of circus posters.

The house looked even more like a colorful picture puzzle on the outside than it had from the inside nine years before. Afraid that our discovery debunked a lot of long-believed lore, we kept our circus posters to ourselves back in 2004. Now here they were again. We needed a bold new theory, one that accommodated both the Underground Railroad and the 1877 posters.

PHOTOS COURTESY MARY HELEN STEFANIAK

A poster advertises the arrival of P.T. Barnum's circus to Iowa City.

PHOTOS COURTESY MARY HELEN STEFANIAK

A poster advertises the arrival of P.T. Barnum's circus to Iowa City.

I found one on a visit to Milwaukee. A historian who was showing me around an old house pointed out that the basement in which we were standing was, at first, the whole house. The two-story frame structure above was added later. Back home in Iowa City, I looked again at our pictures of the excavation in 2004, when the foundation had to be replaced, and saw the different colored layers of dirt that made us think that the limestone walls of the walk-out had been more exposed and less like a “basement” when the house was first built. I remembered that in Keyes’ notes for her book, our house was described as “a three-story house, the first story of stone.”

It seemed clear to me that the ground floor of our house—the saloon level—is the pre–Civil War part. The rest was built on top of that “first story of stone” sometime after 1877. When I looked for evidence to support my theory, a photograph taken on the porch circa 1890 led me to a family history of Louis Englert, the Belgian brewer who built the house. There I learned that Englert’s young friend and fellow businessman Jacob Hotz (1853–1916) was a building contractor. Being a fiction writer and knowing that Hotz would eventually marry Englert’s daughter, Frances (1859–1934), I imagined a story that, in the immortal words of fiction writer Donald Barthelme, “does not contradict what is known.”

Englert would have been in his late 60s when Hotz first suggested the idea. Why not construct a two-story house on top of the low stone building tucked into a hillside just north of town, where Englert had been operating a stagecoach inn and saloon for 20 years already? By 1878, stagecoach travel was limited to nearby towns, but Walter Terrell’s mill across the road still brought in business. There was no reason the Englerts couldn’t keep the saloon open while they enjoyed two new floors of living space above.

Hotz, the young builder, would have done a fine job for his future father-in-law. He would have placed the exterior boards diagonally at the corners to keep the frame house so straight and true that a buyer in 2004 might open the double-hung windows with a single finger. He might have cut the lumber in his sawmill, except for the 12-inch boards recycled from somebody’s roadside barn—the same barn whose owner had gotten free tickets to the circus in 1877 by allowing the display of colorful posters days before the circus train arrived.

And perhaps Frances Englert made her first impression on her future husband while construction was underway. I can see her in the yard with her younger brother Frank and sister Clara, the three of them laughing with delight at the exterior wall going up like a great picture puzzle: part of a horse here and an acrobat there and the “Hippopotamus, Behemoth of Holy Writ,” and elephants cavorting around the name of “P. T. Barnum.”

Iowa Writers’ Workshop graduate Mary Helen Stefaniak (84MFA) recently published her third novel, The World of Pondside. She is professor emerita of creative writing at Creighton University and teaches in the MFA program at Pacific University in Oregon. Stefaniak lives in Iowa City with her husband, John, in the 165-year-old stagecoach inn they restored. This essay is excerpted from her new book, The Six-Minute Memoir: Fifty-Five Short Essays on Life, which was published this past fall by University of Iowa Press.© 2022 MARY HELEN STEFANIAK. USED WITH PERMISSION FROM UNIVERSITY OF IOWA PRESS.