Thirteen Ways of Looking at The Mill

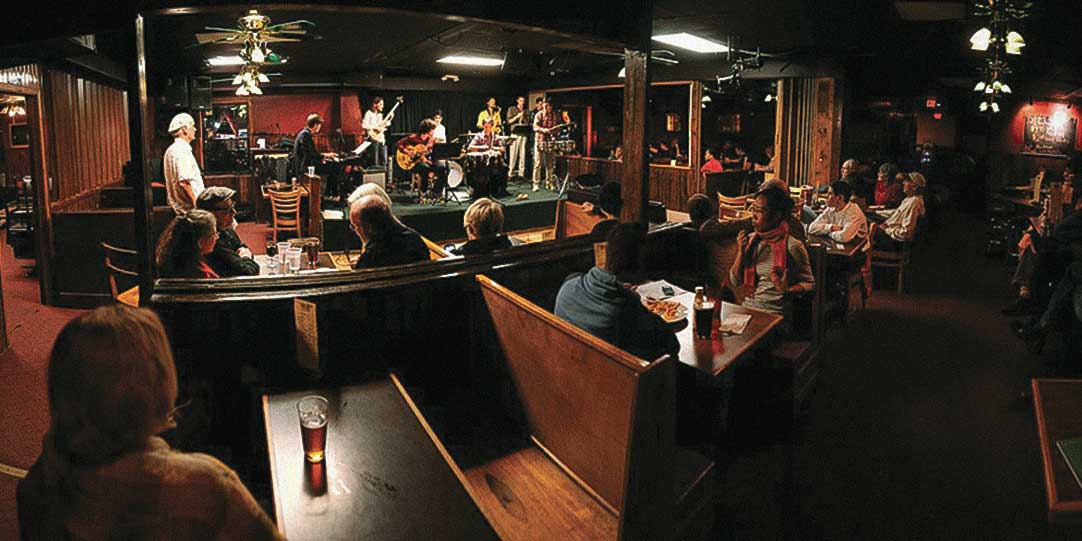

PHOTO: JOSEPH CRESS/IOWA CITY PRESS-CITIZEN

A fixture on East Burlington Street for generations of Iowa Citians, The Mill closed in 2020, and the building was razed earlier this year.

PHOTO: JOSEPH CRESS/IOWA CITY PRESS-CITIZEN

A fixture on East Burlington Street for generations of Iowa Citians, The Mill closed in 2020, and the building was razed earlier this year.

Editor’s Note: A favorite gathering place for Iowa students and alumni over the years, The Mill closed in June 2020 after nearly 60 years of business. In tribute to the Iowa City institution and its place as a cultural hub for many area writers and performers, Iowa Writers’ Workshop alumnus and former Mill bartender Pete Nelson (79MFA) shares his memories in this essay, modeled after Wallace Stevens’ famous poem, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.”

An email tells me the sad news. The Mill is gone. One of Iowa City’s most famous literary watering holes is no more.

I think of how The Mill got me through my first breakup and heartache.

Caused it too.

You should have been there, back in the day…

1.

My first day as a new Mill bartender, one of the local bikers tells me he’ll have a glass of “snoo.”

“What’s ‘snoo?’” I ask.

“Oh, nothing much—what’s new with you?” he says.

Aesthetically, my new workplace … isn’t much. Drop ceiling. Brick-red tiled floor. German beer signs and books and musical instruments and stained-glass and mirrored fixtures and an old brass spittoon for decoration. Wooden chairs and vinyl-upholstered booths, beadboard wainscotting, napkins, and yellow and red squeeze-bottles of mustard and ketchup. The front room has windows. The back room does not, like those casinos where they don’t want you to notice the passage of time.

Down the bar, two construction workers with dust in their hair nurse pints of beer after a hard week.

“There’s only one reason why I could never be a foreman,” one says. “I’m not stupid enough.”

“Aw, you’re stupid enough,” his friend says.

This, I think, is going to be fun.

2.

It’s Monday, late afternoon. The painters are covered with paint and smell like turpentine; you know where the theatre students are sitting because when they talk, they wave their arms above their heads. Mostly, the bar is full of Iowa Writers’ Workshop students, here to continue, under more lubricated circumstances, conversations begun earlier in class. This is where the truth comes out. Famous writers have been here, Raymond Carver and Kurt Vonnegut and Frank Conroy and James Alan McPherson (71MFA).

The customers sit according to discipline. The poets are loud and intense, while the fiction writers are mellow and laugh amicably. Older students drop the names of obscure third-world poets and novelists, and then the new students sneak off to the bathrooms, where they write down the names so they can look them up and sound knowledgeable the next time they hear them.

One night, some workshop students write their order on a napkin and hand it to me. I share it with my fellow bartender, Chuck, who, like me, is a recent graduate of the writing program. We take a red pen and send the napkin back with a helpful critique.

“Would he really order this?”

“This pizza is unearned, and the pineapple raises plausibility issues.”

“You don’t need the ranch dressing—less is more!”

3.

I’m at the end of the bar, chatting with the local health inspector and with Keith Dempster, the legendary owner of The Mill (and president of the BMW Motorcycle Operators of America, hence all the bikers) who is filling his face with handfuls of popcorn kept warm in a glass case beneath a yellow lightbulb. Keith is explaining to me how the safest speed you can travel on the highway is five miles per hour faster than everybody else.

“But, if everybody…” I begin, but I give up because I can’t win.

Keith is brilliant and oppositional and opinionated (but his opinions are all annoyingly well-informed) and ultimately goodhearted, and nobody who meets him ever forgets him. He keeps Vikki Carr’s song “It Must Be Him” on the jukebox to play when he wants to piss off a feminist he’s arguing with, and classical music to drive people away at closing time if turning on the bright fluorescent overhead lights doesn’t do the trick.

Then it’s just me and the health inspector.

Just as I’m about to serve his drink, a cockroach the size of a chihuahua walks down the bar between us. We both see it.

“That’s on the house,” I want to tell the health inspector, but we have strict rules about giving away drinks.

4.

It’s Friday night. The Mill hosts all kinds of music but favors bluegrass and singer-songwriters. There’s a young man with a guitar on stage. His name is Greg Brown. He will go on to sell out theaters and tour nationally and star on Prairie Home Companion, but now he’s just that local kid who sings every Friday night. People eat and talk loudly and don’t know what they’re missing. I sit up front because this guy is KILLING IT, doing, with language and imagery and storytelling, only better, what the poets and fiction writers in the MFA program are trying to do in their verse and prose.

Some nights, after the bar closes, we meet up at Greg’s house, where we play music in the kitchen until the sun comes up, and I feel like I’m living my best possible life.

“I think I first played The Mill in 1968. Keith used to pay me $40 a night,” recalls Brown, who’d tried the Greenwich Village folk scene but preferred Iowa. “Once I got a little better known, he could sell tickets, and then we both did pretty good. I saw him a lot, right before he died. I actually sang at his funeral. I think it was ‘I Come to the Garden Alone.’”

Ordinarily, a musician is more likely to dance on a club owner’s grave than sing at his funeral. Keith was special.

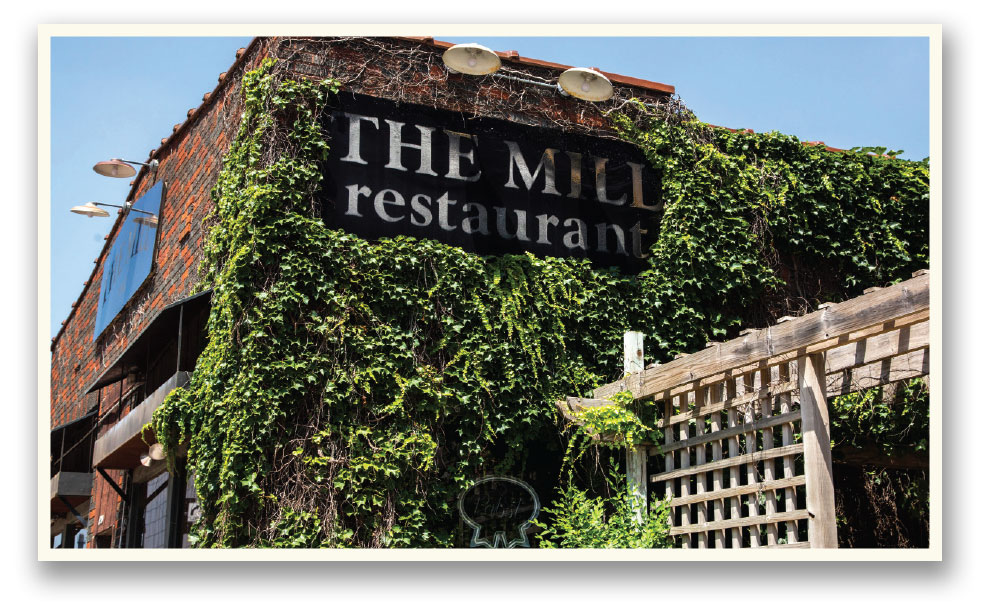

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

The bar and restaurant was an Iowa City institution since opening in 1962.

PHOTO: TIM SCHOON/UI OFFICE OF STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION

The bar and restaurant was an Iowa City institution since opening in 1962.

5.

It’s Feb. 22, 1980. On the television in the corner of the bar, they are broadcasting the hockey game played earlier in the day between the U.S. men’s Olympic hockey team and the Soviets.

None of the men and women in this packed room knows the final score. We hang on every play.

Then, a few minutes into the third period, there’s a station break. A sportscaster who shall remain nameless says: “Great news from Lake Placid—the U.S. wins, 4-3—more news at ten!”

“AAARRRRGH!”

The room erupts in a roar of anguish and dismay.

6.

I’m washing glasses in the sink under the bar when I’m interrupted by an awkward, bespectacled young man who asks where the Mensa meeting is. There is an easy-to-follow map, taped to the front door, that says THE MENSA MEETING IS IN THE BACK ROOM, with arrows indicating where to find the back room, but I patiently show him the way.

He returns 15 minutes later and sheepishly orders 11 White Russians.

They are new at this.

7.

It’s Sunday night. The front room is hushed. Everyone is watching the final episode of a BBC production of Anna Karenina on the TV. When Anna finally throws herself in front of the train, I see bikers and ironworkers, painters and poets, doctors and accountants, ballerinas and librarians, all with tears in their eyes.

We will cry together like this again the night John Lennon is shot.

We share our humanity here. We allow that.

8.

One night, a waitress, “Danielle,” is late for work. When she finally shows up, she’s wearing sunglasses and tells us she “walked into a door.” We know better. We know she lives with her boyfriend, and we know he’s a jerk, and that this is not the first time she “walked into a door.”

“Danielle’s Moving Company” forms, comprising bikers and poets and folk singers. We go out to her house. When her boyfriend comes home from work that night, he sees all his things on the curb. He asks, “Why don’t you mind your own business?” He claims he and Danielle are in love, but it doesn’t matter. We tell him he is leaving town. As he surrenders his house keys, there’s a brief misunderstanding.

Then he walks into a door.

Three times.

That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

9.

If you work at The Mill long enough, you see romantic relationships forming, then dissolving, couples who once held hands under the table later glowering at each other from across the room.

But some are meant to be, as my friend Jane Smiley (75MA, 76MFA, 78PhD) told me.

“I walked into The Mill with friends for maybe the third time—I’m not a drinker,” recalls the novelist, who won the Pulitzer Prize for her novel 1000 Acres. “We find a table and I go to the ladies’ room. The ID card checker, a young man with thick, curly hair and a full dark beard, as I pass, says, ‘I think you are incredibly beautiful.’ I smile.

In the bathroom, I nearly pass out with amazement. No one has ever said that to me.

“When my friends leave, I say I am going to stay for a while to listen to the music. Closing time, I’m still there. The young man asks me if I would like him to walk me home. I nod. On the way to where I am staying, we chat. He’s flirtatious but kind. He says he would like to date me.

“The next day, because it is the ’70s and we are hippy-ish, when my husband comes to pick me up, I say, ‘I’d like to have an affair.’ He says, ‘I’ll think about it.’ The day after that, he said, ‘I don’t think so.’ I say, ‘Then I am leaving you.’ Two days later I move in with the ID checker (and bartender, waiter, and musician). Eventually, we move to a two-room cabin on a hillside near the highway. Woodstove, meals at The Mill. Eventual result—beautiful son and a long-term friendship.”

10.

Ninety percent of all the lust expended in Iowa City on any given night is directed toward The Mill waitresses, who are beautiful and brilliant and self-actualized and unlikely to take crap from anybody.

My favorite is Little Deb, called that because she’s smaller than Big Deb. She is extremely cheerful and friendly and easily distracted, so much so that customers occasionally, waiting for her to bring the bill, get frustrated and walk out without paying, and then she has to make up the difference from her tips. One night, she runs out the door, chasing after a customer who has skipped on his tab, but she can’t catch him. She returns in tears.

Little Deb’s had walk-aways before, but this man was in a wheelchair. He’s a roll-away.

She might have caught him if he hadn’t turned downhill.11.

Eight years after I moved away, I return to The Mill with a friend. Before we enter, I predict who is going to be sitting on which barstool. I get the people right, but the order wrong.

Here is Pappy, who once told me he lost all his teeth because he smiled too much when he was in the Navy, “with all that salt in the ocean air.”

Here is Margret, the pink-haired 80-year-old crossing guard, who makes the bartenders recite the entire beer list before she orders (every single time) Special Export, not because she doesn’t know what she wants, but because she’s lonely and seeks conversation.

Here is Rich, the doctor who plays pinball in the lobby.

Here is Brother John, the long-haired, bearded, head-banded biker, and here is Whale, his larger, long-haired, bearded, head-banded biker brother.

Here is Teri Jean and Diana and Sandy and Ron and Dave and Tall Paul and Chuck and the other Chuck and the other other Chuck. Here is Michelle (oh Michelle), and the Debs.

Here is my family, my sisters and brothers from other mothers.

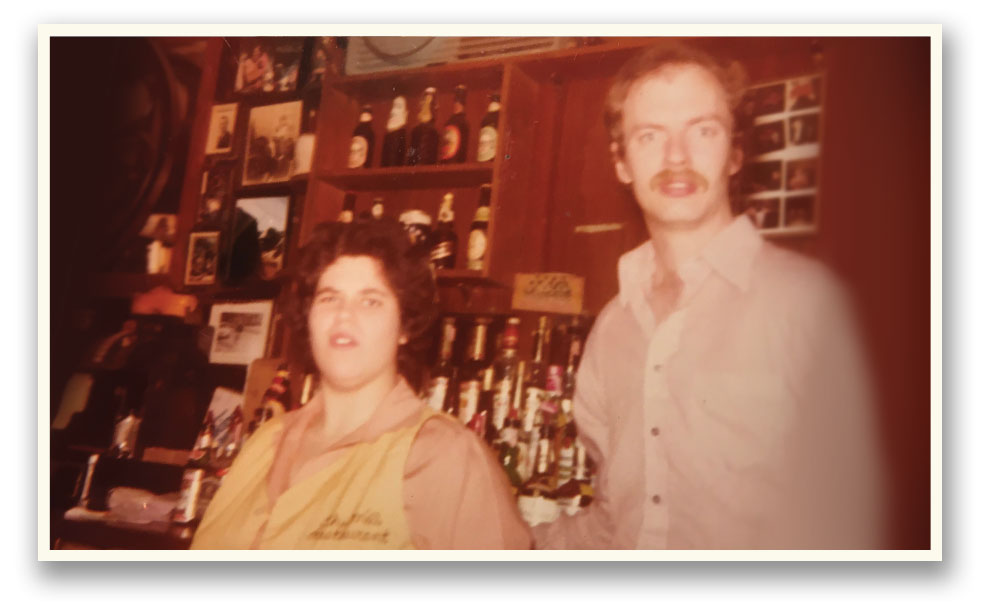

PHOTO: PETE NELSON

Diana and Tall Paul, the manager of The Mill, in the restaurant’s heyday.

PHOTO: PETE NELSON

Diana and Tall Paul, the manager of The Mill, in the restaurant’s heyday.

12.

One of the harsher ironies of growing old is the forlorn bewilderment you feel when you outlive an institution. They are brick and mortar. You are flesh and blood. You’re supposed to go first. Iowa City still has The Hamburg Inn No. 2 and George’s and Dave’s Foxhead and John’s Grocery, but even those won’t last forever.

Maybe institutions die the way people do, bit by bit, a system crash that starts at the cellular level. First the faucet, then the sprinklers, then the plumbing, the furnace, while taxes go up and the rent goes up, and it all cascades to failure. People tried to save The Mill, to have it declared a historic site, but it was too little, too late. It took a plague to kill it.

“The pandemic was just the last straw,” says Marty Christensen, the man who bought The Mill from Dempster and ran it for its last 17 years. “We were tarring the roof every three years, just to keep the leaks to a minimum. After we closed, I couldn’t even drive down Burlington to look at the place. It was an amazing playground for so many people, but it was over.”

Whatever they build on the site is guaranteed to be haunted by the spirits of all of us who grew up there, met our greatest challenges there, sheltered there to weather the storms, found joy there, and sorrow too, and sang there, and danced there.

I’m just one person, with all these memories. Multiply that by the hundreds of thousands of people who passed through those doors since The Mill opened in 1962. Before the TV show Cheers, there was The Mill, an intellectual and a spiritual nexus, a citadel of culture and conversation, of thought and art and political discourse, standing strong in a small quiet corner of a world increasingly populated by unread, unwashed barbarians.

13.

It’s the December before the pandemic, the annual Christmas show. I don’t know it, but it’s the last year The Mill will be open.

I have driven here with my son Jack. He is 18. We are stopping in Iowa City, on our way to Minneapolis to visit my family for the holidays, but it’s important to me. As a parent, you want your kids to know where you came from.

The band is blowing the roof off. They play the blues, but they also play Christmas music, and when they do, we all sing. We are all united in song. We are all happy. This is pagan, and this is sacred.

I don’t drink anymore and my son is too young, but apart from that, we are having a quintessential Mill experience: music, libation, food, community, sharing.

Love.

“I’m so glad I could show you this,” I tell Jack. “This is the best place I’ve ever been.”

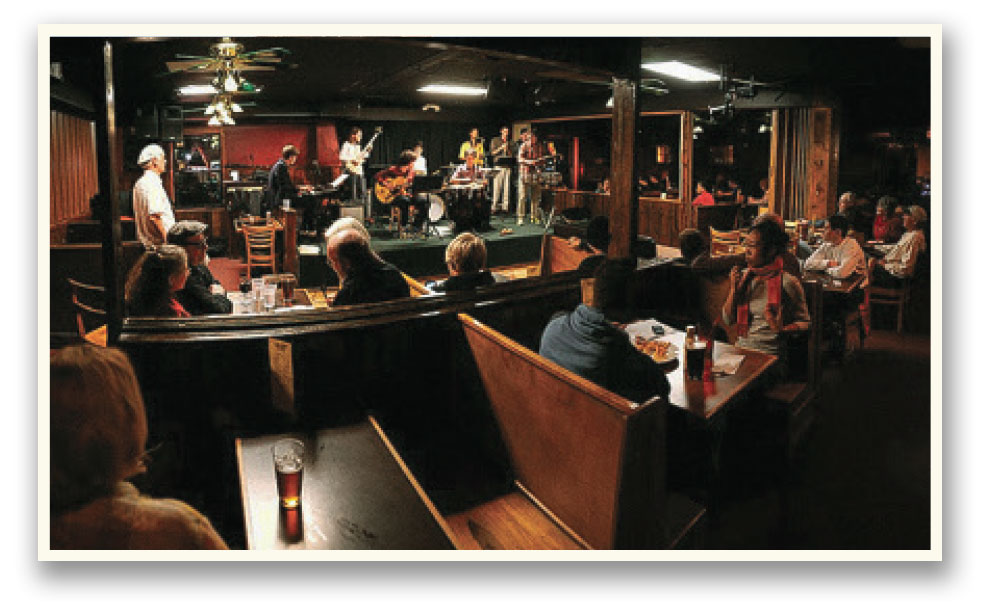

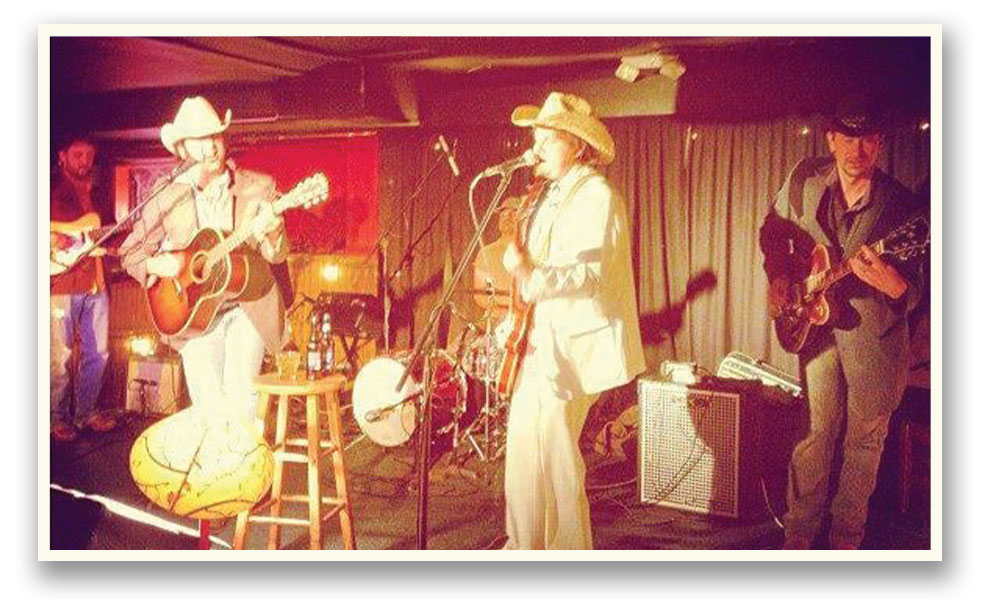

PHOTO COURTESY THE MILL VIA FACEBOOK

Decades of local and touring musicians graced The Mill’s stage.

PHOTO COURTESY THE MILL VIA FACEBOOK

Decades of local and touring musicians graced The Mill’s stage.