At the UI Museum of Natural History, a Paradise Not Yet Lost

In the softly lit space, each bird seems primed to burst into flight at an instant. Laysan albatrosses dance, puffing their chests and pointing their beaks toward a painted sky. Nearby, a black-footed albatross lunges at a companion, while a masked booby preens fluff off its chick. On a rocky cliff, sooty terns bicker over a crab, as a dazzling red-tailed tropicbird floats above it all, surveying the hectic aviary below.

More than a century after it opened to the public, the Laysan Island Cyclorama continues to captivate visitors to the University of Iowa Museum of Natural History. Tucked away in Macbride Hall, the exhibit is a sprawling display containing more than 100 mounted seabirds, hundreds of thousands of wax leaves, and a massive mural of sweeping tropical vistas. While each individual element is eye-catching, their interplay creates an immersive experience. As visitors walk through the wood-paneled entrance, they are whisked away to Laysan Island, a wayward atoll some 4,500 miles from Iowa City.

Like most visitors, Liz Crooks (08BLS), director of the UI Pentacrest Museums, is transfixed by the cyclorama’s vast scope. In recent years, however, she has found it increasingly difficult to appreciate the entirety of the exhibition. Tours with conservators have revealed flaking paint, crumbling wax, and feathers coated in soot—signs of decay from a century on display. “As magical and impressive as it is, once the conservation needs were brought to my attention, I couldn’t unsee it,” she says.

To restore the Laysan Island Cyclorama—one of roughly 30 historic cycloramas still in existence worldwide—Crooks is spearheading an ambitious conservation effort. Like the distant ecosystem it depicts, the cyclorama has become an endangered environment of peeling paint and oily seabirds. “There is no lack of irony there,” Crooks says. “The cyclorama is dedicated to preserving this natural space and now is in dire need of conservation itself.”

And like a true ecological crisis, time is running out for the museum to restore the historic exhibit before Iowa’s piece of paradise is lost.

PHOTOS COURTESY PENTACREST MUSEUMS

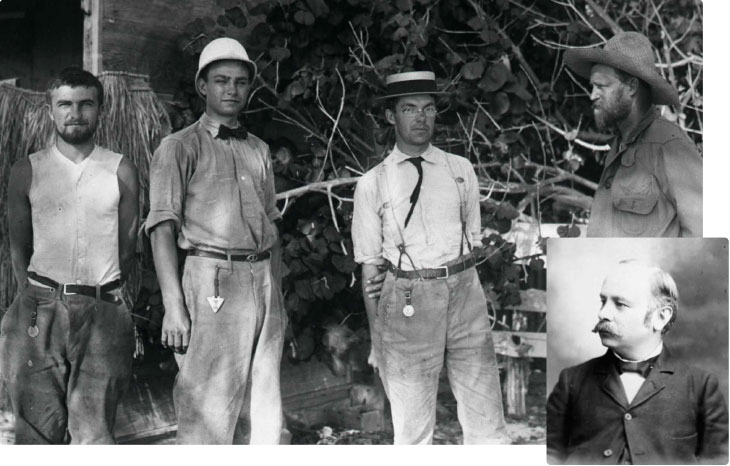

In 1911, university museum curator Charles Nutting (1896BPH, pictured above) sent Iowa students Horace Young (1911BA) and Clarence Albrecht (1914BA), zoology professor Homer Dill, and muralist Charles Corwin (all pictured at top, from left to right) on an expedition to Laysan Island to gather specimens for an exhibit.

PHOTOS COURTESY PENTACREST MUSEUMS

In 1911, university museum curator Charles Nutting (1896BPH, pictured above) sent Iowa students Horace Young (1911BA) and Clarence Albrecht (1914BA), zoology professor Homer Dill, and muralist Charles Corwin (all pictured at top, from left to right) on an expedition to Laysan Island to gather specimens for an exhibit.

More Than a Wild Goose Chase

Charles Nutting’s grand vision for the Laysan Island Cyclorama was hatched in 1902, when he was half a world away from Iowa. In addition to his duties as a UI zoology professor, Nutting (1896BPH) was one of the world’s foremost experts on hydroids, a suite of minute, stinging predators related to jellyfish. His expertise booked him passage upon the U.S. steamer Albatross during a Smithsonian expedition to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. As they trawled the deep sea and described novel species of marine life, the scientists also explored the smattering of remote atolls dotting that stretch of the Pacific.

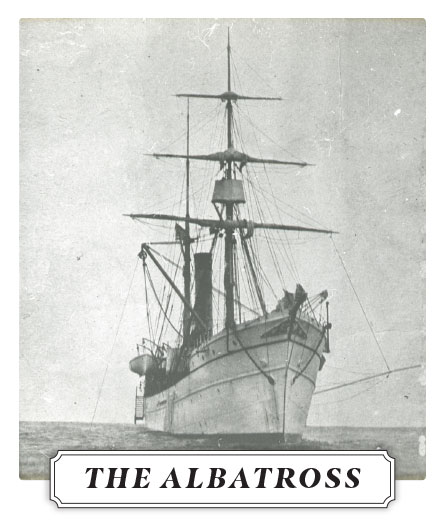

PHOTO COURTESY PENTACREST MUSEUMS

Nutting first developed a fascination with Laysan Island on his 1902 voyage to Hawaii aboard the Albatross.

PHOTO COURTESY PENTACREST MUSEUMS

Nutting first developed a fascination with Laysan Island on his 1902 voyage to Hawaii aboard the Albatross.

That was how Nutting first stepped foot on Laysan Island, a tiny outcrop of sand, coral, and little else. However, the island was far from uninhabited—millions of seabirds treated it as a stopover to breed and rear chicks. As Nutting gingerly navigated the cacophonous crowds, he was rightfully overwhelmed by the sight of 8 million birds crammed onto just 1.5 square miles of island. “For no one...could possibly contemplate this assemblage of avian life without being profoundly moved by the experience,” he would later write in a 1909 edition of The Iowa Alumnus.

Nutting wanted nothing more than to introduce his fellow Iowans to the natural splendor of Laysan. But he knew his words and grainy photographs could only do so much. Many of his readers had never seen saltwater, let alone contemplated the sight of thousands of albatrosses swaying in the tropical breeze, so Nutting undertook the ambitious task of bringing Laysan Island to Iowa.

Nutting already had a venue. In 1886, he became curator of the university’s Cabinet of Natural History, the oldest academic natural history museum west of the Mississippi River. In short order, he dusted off specimens that had languished for decades in storage and launched several far-flung expeditions to collect new material. To help exhibit the museum’s growing stockpile of specimens, Nutting hired the pioneering taxidermist Homer Dill in 1906.

Dill, a UI assistant professor of zoology, had never created a display approaching the magnitude of what Nutting envisioned for the Laysan exhibit. A standard diorama didn’t adequately encompass the sheer spectacle of Laysan Island, so they embraced an ambitious style of exhibition known as the cyclorama. Often wrapped inside a 360-degree mural, cycloramas (which are also called panoramas) were the virtual reality of their time, immersing visitors within the display. By melding the background mural with three-dimensional objects in the foreground, cycloramas gave the viewer a sense of contrast, creating the illusion of distance.

Cycloramas peaked in popularity in the late 19th century, when their sweeping displays became ideal for depicting epic military battles and whale hunts. Nutting, however, had a much different subject matter in mind. He sought to co-opt the epic vistas to capture a serene, tropical island teeming with birds instead of soldiers. The Laysan Island Cyclorama would be the first of these exhibits in the world to focus solely on a single ecosystem.

Nutting and Dill still had to procure an island’s worth of birds. The cost of a Hawaiian expedition was staggering, which forced Nutting to do a decade of impassioned fundraising. To ensure Laysan remained in the Iowa City zeitgeist, he lectured and wrote frequently on the wonders he had witnessed. During one 1909 lecture, the Iowa football team even performed a skit to raise money for the expedition.

By 1911, Nutting had secured enough funding to send Dill, two Iowa students, and an artist to Laysan. They were instructed to collect everything they found, from bird eggs to lumps of coral. However, the expedition hit an unforeseen snag as soon as Dill reached the island—there appeared to be little left to collect.

The “clouds of birds” Nutting described had all but vanished. Instead, Dill’s team was greeted by bleached bones and hacked-off albatross wings—the visceral evidence that Japanese feather poachers had recently raided the island. In total, their bloody excursions had slaughtered some 300,000 birds on Laysan, including half of the island’s albatross population.

A horde of invasive rabbits had also become entrenched on Laysan. “At times there are so many ears protruding, they resemble a vegetable garden,” Dill remarked in his expedition report. Introduced by the guano miners who once harvested the island’s bird waste as a fertilizer, the rabbits were devouring Laysan’s native shrubs and grasses, stripping the island of nesting material and the roots that anchored the sand in place. As the plant coverage vanished, shifting sands buried underground nesters and the island’s insect population plummeted, dooming several species of insectivore birds found nowhere else on earth.

While circumstances initially appeared bleak, Dill’s team managed to procure plenty of material for the exhibit. Most importantly, they collected nearly 400 bird specimens representing all 23 species that frequented the atoll. As they gathered the birds, they also took aim at the island’s invasive rabbits. Dill notes in his official report that the rabbits made for good eating. However, the team only made a dent in the population, and the plague of rabbits would last until 1923. This proved too late for several endemic species of birds, like the spindly Laysan rail and the ruby-red Laysan honeyeater, who succumbed to extinction.

In total, the team used boats and trains to ship 36 crates stocked with everything from terns to gravel across the Pacific and to the Midwest. However, once Dill and the expedition’s spoils returned to Iowa City, the real work began.

Utilizing his nascent museum studies program (the oldest such university program in the country), Dill and his students took years to create the exhibit. They posed 106 of the bird skins into dynamic positions around the display and molded 500,000 individual leaves out of wax. Charles Corwin, the expedition’s artist and a noted muralist at Chicago’s Field Museum, crafted a colossal mural from his field sketches. Altogether, the mural is 138 feet long and 12 feet high and depicts hundreds of birds to compliment the specimens in the foreground.

When the exhibit opened to the public in 1914, Iowans were finally able to experience Nutting’s vision firsthand. Museum visitors saw the terns and half expected to feel “the air quiver with their piercing shrieks,” as Nutting had described it. Nearby, they witnessed the bizarre spectacle of frigate birds inflating their large air sacs, which reminded Nutting of “the brilliant red toy balloons that delighted our childhood.” Corwin’s mural gave life to the “the snow-white coral sand, the dark green vegetation, and the intense blue of the tropic sky.” Together, Nutting and Dill had brought a slice of a tropical paradise to Iowa.

Race Against the Clock

Behind the glass, this avian paradise has remained frozen for more than a century. Brown noddies seem to bob their heads in the breeze, as petrels peek out of their burrows and bushy albatross chicks cozy up with parents. A discerning eye even catches Laysan honeyeaters bouncing from flower to flower among the throngs of boisterous seabirds.

At its core, the Laysan Island Cyclorama is an environmental time capsule, preserving a glimpse of an island unburdened by feather poachers and ravenous rabbits. In a similar sense, the exhibit itself has also become an artifact. Over the decades, the only changes to the display have been the replacement of the original pond material and the addition of interpretive panels and speakers that project recordings of each bird’s call. Behind the glass, everything is almost exactly how Nutting and Dill left it.

Unfortunately, their display has begun to wilt. The cyclorama sits in a corner of the museum’s Hageboeck Hall of Birds where there is no ventilation and the temperature fluctuates wildly. According to Crooks, much of the exhibit is also covered in a fine layer of soot from when the building was lit by gas lamps. Bright white albatross feathers are now drab shades of gray. Water leakage has warped parts of the mural. Other spots are peeling. To protect the specimens from destructive pests, Dill likely used arsenic—a carcinogenic chemical that taxidermists once commonly applied to their work. Crooks believes the toxin is likely sprinkled into the cyclorama’s sand and gravel.

Even the birds are causing decay. “These birds are waterfowl, so they are very oily,” Crooks says, referencing how many seabirds ooze oils to keep their feathers waterproof. Though prepared a century ago, they continue to exude oil, which Crooks says dulls their colors and damages other parts of the display. In this way, Crooks contends that the cyclorama is, in essence, “destroying itself.”

The growing list of eyesores may seem overwhelming. However, the museum staff stresses that a restoration project is possible if the museum can raise between $500,000 and $750,000 within the next five years. Establishing heating, cooling, ventilation, and humidity control is paramount to the effort, according to Jessica Smith (14BA), the museum’s communications coordinator. Until the underlying environment is stabilized, brushing soot off of birds will do little good.

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

The Laysan albatross and red-tailed tropicbird are just two of the many birds represented in the cyclorama.

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

The Laysan albatross and red-tailed tropicbird are just two of the many birds represented in the cyclorama.

Smith likens the cyclorama to a “functioning ecosystem” as complex as the island environment it depicts. Each of its elements seem to affect another, making it crucial that restoration is a coordinated effort. If the museum raises the funds, they envision groups of conservators working on the cyclorama for weeks at a time, brightening up drab seabirds and cleaning Corwin’s mural inch by inch.

While the effort to save it seems herculean, the Laysan Island Cyclorama retains an international importance as one of the few intact cycloramas left. As museums began incorporating film into their displays in the early 20th century, the sprawling exhibits quickly went out of style and many were dismantled to make room for other attractions. The only traces of these lost cycloramas are splotchy newspaper clips.

This makes the Laysan Island Cyclorama a rarity—and cyclorama enthusiasts around the world have taken notice. In recent years, Crooks and the museum have become involved with the International Panorama Council, a Swiss nonprofit dedicated to the conservation of cycloramas around the world. In 2023, the entire cyclorama community will converge in Iowa City, when the IPC hosts its annual conference at the UI Museum of Natural History. “People are willing to come from all over the world—Turkey, Luxembourg, Australia,” Crooks says. “They’re coming here to see something that is in Iowa’s own backyard.”

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

A male magnificent frigate bird (at left) attracts a mate with its red inflatable throat pouch, while adult and juvenile black-footed albatrosses (at right) flock together in the UI exhibit.

PHOTO: JOHN EMIGH

A male magnificent frigate bird (at left) attracts a mate with its red inflatable throat pouch, while adult and juvenile black-footed albatrosses (at right) flock together in the UI exhibit.

Crooks hopes the exposure will aid in their effort to restore the cyclorama. To her, the exhibit is much more than an attraction; it is an educational tool that has inspired an appreciation for nature in generations of local children and UI students—including Crooks herself. “It’s a very special place to me,” says Crooks, who graduated from the museum studies program founded by Dill and has now worked in Nutting’s former office for three years. While Nutting and Dill left behind the cyclorama, Crooks hopes her legacy is tied to saving the exhibit.

"We are at a critical juncture—the cyclorama needs to be conserved if it is to survive for future generations."—Liz Crooks, Director of Pentacrest Museums

However, the clock is ticking. “We are at a critical juncture—the cyclorama needs to be conserved if it is to survive for future generations,” Crooks says. She estimates that in five years, the cyclorama will likely be unsalvageable.

Like Nutting at the turn of the century, she and the museum have set out to tirelessly fundraise. Hitting the lecture circuit is no longer enough (although Smith stresses that if the Iowa football team wants to put together another sketch show, “we will gladly sponsor that”); Crooks encourages the university and alumni community to experience the cyclorama in person.

Crooks, like Nutting before her, believes that standing amid the albatrosses, terns, and shearwaters can spark a passion for the fragile nature of the distant island. She hopes that will also be enough to preserve the paradise a little closer to home.

Jack Tamisiea is a science writer based in Washington, D.C., who covers natural history and environmental issues. Tamisiea's work has appeared in The New York Times, National Geographic, Scientific American, Hakai Magazine, Johns Hopkins Magazine, and many others. Tamisiea is also the son of Iowa alumnus John Tamisiea (87BBA) and grew up an avid Hawkeye fan.