A young woman drives a tractor to the threshing machine. Although farm work was often divided along gender lines, women would help in the fields and many were skilled at operating machinery.

A young woman drives a tractor to the threshing machine. Although farm work was often divided along gender lines, women would help in the fields and many were skilled at operating machinery.

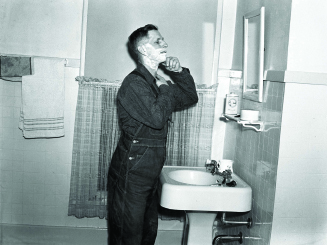

Farmer Ralph Curtis of Montrose, Iowa, shaves in his bathroom after electricity was installed in 1945. Farm electrification rose from 14 percent in 1935 to 90 percent in 1950.

Farmer Ralph Curtis of Montrose, Iowa, shaves in his bathroom after electricity was installed in 1945. Farm electrification rose from 14 percent in 1935 to 90 percent in 1950.

In overalls and a collared work shirt, the Iowa farmer stood at his bathroom sink and looked in the mirror. He lathered up his face, leaned in with his razor, and began his daily whisker harvest. A few feet away, A.M. “Pete” Wettach squinted through his camera and released the shutter, capturing a milestone on the Ralph Curtis farmstead. Electricity had finally arrived in this corner of Lee County, and a new bulb above the sink brightened Ralph’s morning shave before he headed into the fields.

The scene was among the tens of thousands preserved by Wettach’s lens during the Great Depression and postwar years in rural Iowa—a period when electricity and mechanization revolutionized the American family farm even as economic hardships bore down. The horse-drawn plows of the pioneer days gave way to steel-wheeled tractors, indoor plumbing replaced outhouses, and ice boxes were swapped out with refrigerators.

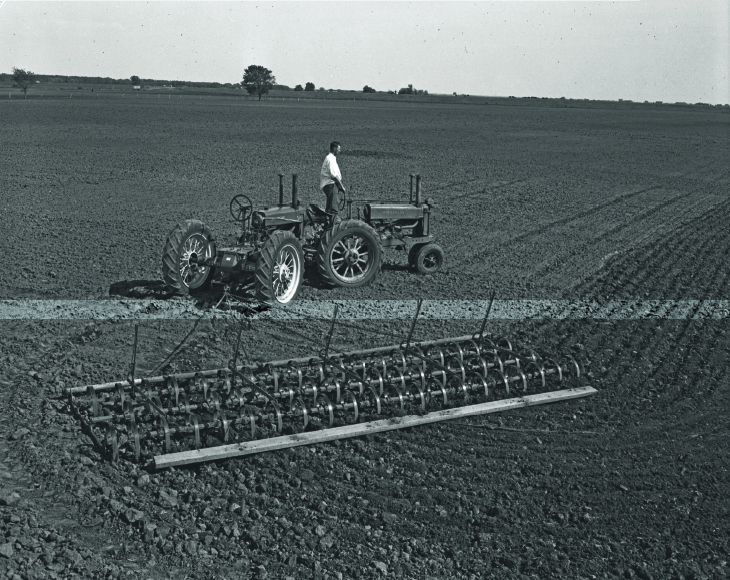

A pair of hitched John Deere tractors guide what appears to be an old harrow too heavy for just one tractor. Farmers had to be resourceful in adapting their horse-powered implements to work in tandem with their new machinery.

A pair of hitched John Deere tractors guide what appears to be an old harrow too heavy for just one tractor. Farmers had to be resourceful in adapting their horse-powered implements to work in tandem with their new machinery.

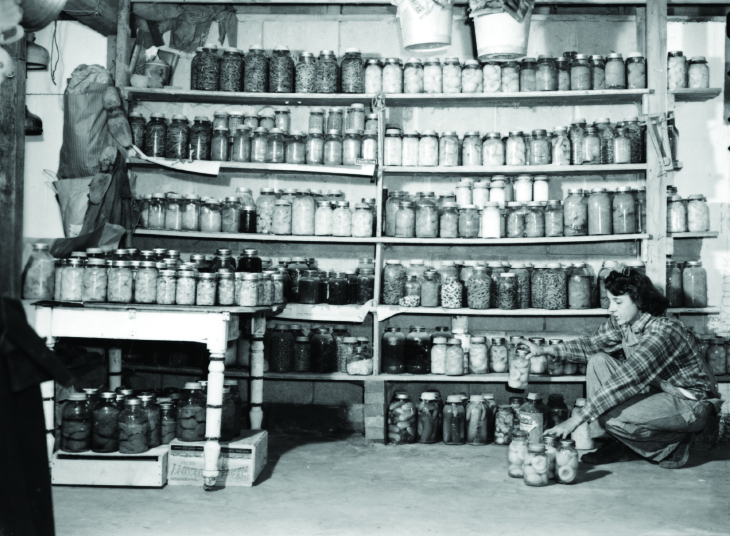

A woman arranges canned goods on her basement shelves. Farm meals would often include vegetables from the garden and canned orchard fruit—along with fresh eggs, milk, and poultry.

A woman arranges canned goods on her basement shelves. Farm meals would often include vegetables from the garden and canned orchard fruit—along with fresh eggs, milk, and poultry.

A.M. “Pete” Wettach poses with his Graflex camera in 1944. Growing up in New Jersey, Wettach was fascinated with rural life. He moved to the Midwest in 1919 to study agriculture at Iowa State College in Ames and tried his hand at farming in his younger years. Forced to find work elsewhere during the Great Depression, Wettach became a county supervisor for the Farm Security Administration. His passion for rural America was reflected in his prolific work as a freelance photographer for magazines and newspapers across the country.

A.M. “Pete” Wettach poses with his Graflex camera in 1944. Growing up in New Jersey, Wettach was fascinated with rural life. He moved to the Midwest in 1919 to study agriculture at Iowa State College in Ames and tried his hand at farming in his younger years. Forced to find work elsewhere during the Great Depression, Wettach became a county supervisor for the Farm Security Administration. His passion for rural America was reflected in his prolific work as a freelance photographer for magazines and newspapers across the country.

A loan officer with the Farm Security Administration, Wettach (1901-76) crisscrossed Iowa’s dusty roads in the 1930s and 1940s to help renting farmers purchase their land through government programs. Wettach was also a freelance photographer who traveled with his large-format Graflex camera in tow and sold images to farm magazines, newspapers, and other publications. Along his travels, Wettach photographed everything from families cooking meals atop new stoves to early combines rolling through the fields. The close relationships he developed with his clients resulted in often intimate snapshots of their lives. For historians, Wettach’s photography provides a unique document of rural Iowa during an era of hardship and change. For the rest of us—as you’ll see in the coming pages— the photos also provide a nostalgic window into time and place as idyllic as it was hardscrabble.

Wettach’s work is the subject of a traveling UI Museum of Art exhibition titled Farm Life in Iowa, which was on display in Maquoketa earlier this spring and opens at the Herbert Hoover Presidential Museum and Library in West Branch in early 2018. The installations are part of the UIMA’s Legacies for Iowa program, which is supported by the Matthew Bucksbaum family and shares the university’s art collection in communities across the state.

The museum exhibitions spotlight a collection of photographs that had sat unnoticed for decades—until their serendipitous discovery in 1999. That was the year the late Leslie Loveless, then an editor at the UI’s Institute for Rural and Environmental Health, recovered six old boxes of postcard-sized, black- and-white negatives from the bottom of an Oakdale Campus filing cabinet. The images that emerged—at once visually striking, artfully composed, and pristine in quality—revealed a bygone era. There was the backbreaking toil of farm life and the desolation of drought and the Depression. At the same time, many of the photos were Rockwellian—children picking vegetables, mothers rolling out pie crusts, and fathers kicking back with an evening newspaper.

Horses draped with fly nets wait to pull a wagonload of oat bundles. During World War II, 690,000 tractors replaced two million horses and mules on American farms. By 1955, there were more tractors than farm horses in the U.S.

Horses draped with fly nets wait to pull a wagonload of oat bundles. During World War II, 690,000 tractors replaced two million horses and mules on American farms. By 1955, there were more tractors than farm horses in the U.S.

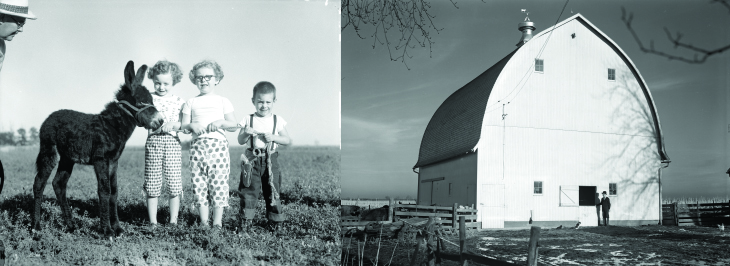

LEFT: The children of Albert Nau of Mount Pleasant, Iowa, pose with their new pet, a four-day-old Mexican burro colt. When the burro was older, it was hitched to a buggy to take the children to school. RIGHT: A gothic-style dairy barn, circa 1935.

LEFT: The children of Albert Nau of Mount Pleasant, Iowa, pose with their new pet, a four-day-old Mexican burro colt. When the burro was older, it was hitched to a buggy to take the children to school. RIGHT: A gothic-style dairy barn, circa 1935.

Atop one of the boxes, Loveless found a label: “A.M. Wettach; Agricultural Photographer; Mount Pleasant, Iowa.” The surname led her to Wettach’s son, Robert Wettach, 56MD, a family doctor in Mount Pleasant, who had stored his father’s entire collection of prints and negatives in his basement since Pete’s death 23 years earlier. Working with Loveless, Robert donated the bulk of the estimated 50,000 negatives, maybe more, to the State Historical Society of Iowa. In 2002, Loveless published a book of Wettach’s photos titled A Bountiful Harvest through the UI Press.

Robert Wettach, Pete’s son, wears a cowboy hat as he feeds chickens in a barnyard, circa 1940. Robert went on to medical school at the UI and became a family doctor in Mount Pleasant.

Robert Wettach, Pete’s son, wears a cowboy hat as he feeds chickens in a barnyard, circa 1940. Robert went on to medical school at the UI and became a family doctor in Mount Pleasant.

LEFT: A boy is pictured on the farm in the late 1930s. For children, daily chores included feeding animals, gathering eggs, milking, herding stock, and fieldwork. RIGHT: A young boy holds a corncob in a 1940s pigpen.

LEFT: A boy is pictured on the farm in the late 1930s. For children, daily chores included feeding animals, gathering eggs, milking, herding stock, and fieldwork. RIGHT: A young boy holds a corncob in a 1940s pigpen.

Mary Bennett, 76BA, 85MA, special collections coordinator for the State Historical Society of Iowa, says Wettach’s ties to a community modest in both manner and means resulted in a more authentic depiction of Iowa than the Farm Bureau poster families. Says Bennett: “These were the people who were converting a chicken coop to live in, or families scrambling to grow vegetable gardens to supplement their income. It’s a socioeconomic portrait that we wouldn’t have otherwise.”

UIMA Senior Curator Kathleen Edwards says that Wettach’s photos countered the notion of rural backwardness—a popular view among urbanites of his era. Instead, the ingenuity and resourcefulness of Wettach’s subjects mirrored the ideals of 19th century Western European agrarian philosophy, such as self-determination, independence, religious freedom, family values, and the nobility of a life among nature.

Says Edwards: “There was the belief that there was political and economic strength for those who worked the land.”

Even with Loveless’ book and the UIMA exhibitions, the bulk of Wettach’s work remains unexplored. Only a small fraction of his photos have been examined, let alone exhibited or published, and the large-format negatives sit sealed in their original boxes on shelves in the Historical Society’s Iowa City Research Center awaiting future historians. “I would say we’ve only begun to realize how magnificent the collection is,” says Bennett.

LEFT: A woman hangs laundry on the line in the 1950s. RIGHT: After World War II, new technology made its way into Iowa farmhouses, including electric-powered refrigerators, washing machines, coffee pots, and—as seen here in the 1950s—televisions.

LEFT: A woman hangs laundry on the line in the 1950s. RIGHT: After World War II, new technology made its way into Iowa farmhouses, including electric-powered refrigerators, washing machines, coffee pots, and—as seen here in the 1950s—televisions.

Men pile hay bales high with the help of a conveyor in the 1940s. Automatic balers were welcome time-savers in the fields, replacing the tedious work of hand-tying hay.

Men pile hay bales high with the help of a conveyor in the 1940s. Automatic balers were welcome time-savers in the fields, replacing the tedious work of hand-tying hay.

Photographic information from A Bountiful Harvest (University of Iowa Press, 2002, www.uipress.uiowa.edu/books/2002-fall/lovbouhar.html) and the State Historical Society of Iowa.