Several years ago, one of Byron Preston’s friends dug up a small metal ball from the dirt floor of his Virginia barn. Seemingly insignificant, it reinforced Preston’s claim that “little objects can tell amazing stories.”

In this case, the incredible tale described a defining period in American history that still resonates today. The piece of metal was a Civil War musket ball—and its curious indentations spoke to the agony of injured soldiers who underwent amputations without anesthetic. In blood-stained, dirty tents, surrounded by the screams of their suffering comrades, they could only bite down on the metal as surgeons hacked away injured limbs with metal saws.

Some 150 years after the firing on Fort Sumter touched off a conflict unlike any other, the Civil War is still all around us, buried in the national subconscious like a festering, unrecoverable bullet. Its influence is felt in troubled race relations, the ongoing struggle over federalism versus states’ rights, and increasingly uncompromising, rigid attitudes among politicians.

“The Civil War defined who we are as a nation in terms both good and bad,” says Preston, 90BA, curator of a new UI exhibit timed to coincide with the sesquicentennial of the conflict. “It led to acts of great courage and sacrifice and also barbarism and savagery.”

Despite an overwhelming amount of information in academic textbooks, popular novels, movies, and TV series, many myths and misunderstandings persist about this cataclysm. The exhibit hopes to educate Iowans about the state’s role in the conflict, as well as the ways in which ordinary citizens became embroiled in an extraordinary event.

It tells the tales of such Iowans through diaries, photographs, and personal items like razors and cooking utensils. “Gone to See the Elephant: The Civil War through the Eyes of Iowa Soldiers” draws its title inspiration from a popular 19th century saying. As early American pioneers headed west into unexplored terrain, they expressed their excitement and anticipation through a euphemism: they were going to see an elephant, a rare, exotic creature they’d heard of but could scarcely imagine.

After the war, veterans would exclaim, “I’ve gone to see the elephant, and, by God, I never want to see another one!”

History of the Common Man (and Woman)

PHOTO COURTESY: HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MARSHALL COUNTY

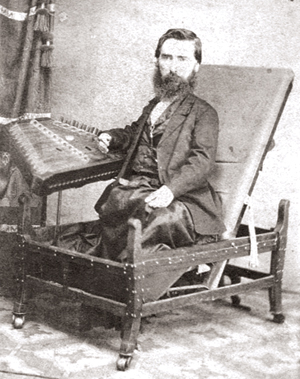

Former UI student Nick Messenger was praised for his bravery on battlefields that thundered with "the awful din of a thousand cannon—a clamor fit to wake the dead." Messenger returned home with his dreams and his body shattered.

PHOTO COURTESY: HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MARSHALL COUNTY

Former UI student Nick Messenger was praised for his bravery on battlefields that thundered with "the awful din of a thousand cannon—a clamor fit to wake the dead." Messenger returned home with his dreams and his body shattered.Faced with a subject matter both overwhelmingly large and yet also so generally familiar to most Americans, Preston decided to focus on the lesser-known stories of individuals caught up in this epic sweep of a nation’s history. As such details are often less documented, he spent much time combing through local newspapers’ commemorative editions or working directly with families or small museums to collect carefully preserved mementoes.

He wanted to get away from top-down history—well-worn facts and figures about battles, tactics, and leaders. Instead, he wanted to show it from the ground up; to relate the everyday experiences of common soldiers who went away to war, walked through hell, and emerged on the other side forever changed.

Nick Messenger certainly found his life transformed by his experiences in the Battle of Vicksburg and in the Shenandoah Valley campaign. One of the Iowans featured in the Old Capitol exhibit, Messenger abandoned his UI studies at the age of 22 to enlist. He became a sergeant in the 22nd Iowa Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which suffered an 82 percent casualty rate.

Although one of the lucky ones to survive, Messenger returned home after three years with the searing torment of scars and shattered bones, as well as memories of two months as a prisoner of war. Forced to abandon the plans for a teaching career that had taken him to the University of Iowa, he became a county recorder. In his Marshalltown office, he displayed the uniform riddled with bloodstains and bullet holes.

PHOTO: STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF IOWA/IOWA CITY, IOWA

The Civil War changed Annie Wittenmyer's life forever. Her courage and determination to aid wounded soldiers earned her the gratitude and admiration of General Ulysses S. Grant.

PHOTO: STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF IOWA/IOWA CITY, IOWA

The Civil War changed Annie Wittenmyer's life forever. Her courage and determination to aid wounded soldiers earned her the gratitude and admiration of General Ulysses S. Grant. Photographs taken in Messenger’s later years show a solemn-faced man with soulful eyes, twisted and truncated arms, and folds of empty fabric in place of his legs. Invalided by his service, he had to be carried around for the rest of his life. It’s hard to reconcile this diminished, weary man with the gallant youth who dodged a hail of bullets to scale the fort walls at Vicksburg. There, he planted the Union flag, which blew defiantly in the breeze over the battlefield. The Marshalltown Statesman later paid tribute to him as a soldier brave and true, and one who poured out his blood upon the altar of his country, that the Nation might live.”

Messenger’s experience with battles and wounds is a familiar war story. Leslie Schwalm, a history professor in the UI College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, points out that many people overlook another side of the conflict. Heroic acts on the battlefield took up only a small portion of soldiers’ lives; dull, menial tasks like hauling supplies and digging trenches filled the bulk of their days, while diseases—especially diarrhea caused by dysentery and typhoid—claimed far more lives than bullets.

Plus, male soldiers weren’t the only ones caught up in those tumultous years. Annie Wittenmyer, an Iowa widow, earned this accolade from General Ulysses S. Grant: “No soldier on the firing line gave more heroic service than she did.”

Wittenmyer, also featured in the exhibit, originally became involved with the war effort by helping tend wounded soldiers in a hospital in the Mississippi river town of Keokuk in southeastern Iowa. After discovering that troops—including her brother, David—often subsisted on rotten food, lacked warm clothing, and were lucky to survive harsh, rudimentary medical aid, she became an ardent champion for their improved care.

Not content with raising funds and supplies (some $150,000 from Iowa alone) and writing letters to the families of injured and dead soldiers, Wittenmyer risked her safety on the frontlines. Clad in the dark, cumbersome, full dresses of the time, with her hair braided on top of her head and covered by a hat and veil, she insisted on visiting Vicksburg during a major siege. Confederate troops let loose volleys of bullets as she rode her horse to an improvised field hospital, yet she completed her mission. She reported the dire situation to General Grant, who immediately ordered the hospital moved to a safer distance.

Wittenmyer’s wartime battle was not only with enemy bullets and the diseases that weakened soldiers; she also fought the prejudices of men (including the state governor) who underestimated Iowa women’s ability to efficiently organize soldiers’ relief under her leadership.

A White Man’s War

PHOTO above courtesy: Daniel G. Clark

Alexander Clark fought against discrimination before, during, and after the Civil War.

PHOTO above courtesy: Daniel G. Clark

Alexander Clark fought against discrimination before, during, and after the Civil War.Although often portrayed as a moral crusade to end slavery, the Civil War escalated initially and primarily as a pragmatic effort to preserve the Union. Alexander Clark discovered that harsh truth first-hand. The son of emancipated slaves, Clark worked his way up from a barber to the second African-American graduate of the UI’s law school (following in the footsteps of his son, Alexander, Jr.).

Before the war, along with his wife, Catherine, a former slave, he defended fugitive slaves from recapture and petitioned the Iowa state legislature for civil rights.A brilliant speaker who earned the nickname “the colored Orator of the West,” he traveled across the country and inspired many people.

Yet, when he approached Iowa Governor Samuel J. Kirkwood in 1862 and offered to raise a company of black volunteers, he was summarily dismissed with the words, “It’s a white man’s war.”

Only after President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 did slavery become a defining issue in the war—and Clark was able to recruit some 1,153 African-American men from Iowa, Minnesota, and Missouri to form the 1st Iowa Volunteers (later known as the 60th U.S. Colored Infantry).

As the UI exhibit shows, Clark’s campaigns against discrimination didn’t end when the war did. Even after the Union’s military and moral victory, Clark continued to fight for basic rights in Iowa, where schools remained legally racially segregated until 1874. In 1867, he and Catherine took a case all the way to the Iowa Supreme Court to ensure that their daughter, Susan, could attend public school in Muscatine.

“Not being enslaved and not having full civil rights are two very different things,” says Schwalm. Indeed, despite what historian Robert Penn Warren termed the “treasury of virtue” that the North eagerly claimed after the war, African-Americans often suffered serious discrimination at the hands of their liberators. Even after African-Americans were granted the right to vote in the South during Reconstruction, many Northern states, struggling to accept an influx of some 100,000 former slaves, refused to follow suit.

The Unknown Soldiers

Last year, historian J. David Hacker published an article in the New York Times making the case for his recent research that revised the Civil War death toll upwards by 20 percent, from 618,000 to 760,000—the equivalent of 10 million Americans in today’s population. Despite decades of academic work and debate, such critical aspects of the conflict remain surprisingly nebulous.

PHOTO: STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF IOWA/IOWA CITY, IOWA

David Davis was one of many UI students who answered the call to battle—and paid with their lives.

PHOTO: STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF IOWA/IOWA CITY, IOWA

David Davis was one of many UI students who answered the call to battle—and paid with their lives. When Preston began researching “Gone to See the Elephant,” he soon realized the existence of what he calls “ghosts”—everyday people who played a significant part in this great national event yet are a shadowy presence in most history books.

“Then, as now, some people died in war and no one ever found out what happened to them,” he says. Indeed, most Civil War troops came from small, tightly knit communities; the prospect of dying on a far-flung battlefield and lying unmourned in an unmarked grave far from home provoked a particular horror.

In 1864, two years after he left the UI to go and “see the elephant,” David Davis found himself among the Union troops headed from Atlanta to Savannah on General Sherman’s infamous “March to the Sea.” For three long days, under a relentless hail of bullets and cannon fire, he rallied his comrades from the 22nd Iowa around the Union flag at the Third Battle of Winchester (Virginia). Then, in an instant, a musket ball shattered his temple, and Captain Davis fell dead on the battlefield. Mourned by his fellow troops and honored by his commanding office as a “gallant officer and estimable man,” the former UI chemistry student was buried on the field at Winchester.

Lost to family and friends, Davis could only haunt their memories. Today, his final resting place is unknown—but his sacrifice isn’t forgotten. Earlier this summer, as Byron Preston gathered Civil War information and artifacts, he knew that he wanted to commemorate Davis. For several weeks, under the curious gaze of his neighbors, he built a makeshift pinewood coffin in his driveway. It was time to lay a ghost to rest.

More on the War

UI history professor Leslie Schwalm wrote Emancipation's Diaspora: Race & Reconstruction in the Upper Midwest , which assesses emancipation as a national event, with dramatic impact on ideas about rights and freedom in places like Iowa City, Keokuk, and Davenport. One chapter is also devoted to the story of Iowa's black regiment, the 60th U. S. Colored Infantry.

She recommends these additional resources for anyone interested in learning more about the Civil War:

Cold Mountain—both the 2003 film and the 1997 historical novel by Charles Frazier, which received the U.S. National Book Award for Fiction.

Jubilee—a fictionalized account of author Margaret Walker's own family history about how an enslaved girl experienced the war and its aftermath.

The Civil War, A Concise History—a very readable book by Louis P. Masur that offers the best and briefest scholarly overview.

http://civilwardc.org —offers maps, visual materials, and historical documents to help make sense of how the war hit Washington, D.C. A great example of digital humanities, it offers clear instructions on how viewers can engage with the material and pursue answers to their own questions about the war.

Voices from the War

"Our horses have plenty to eat but our Rations of Hard Bread is scarce."

In 1864, Union soldier John Paisley of Ohio wrote this line in his diary. Almost 150 years later, a University of Iowa librarian sent it out via Twitter.

The tweet is just one example of how libraries staff make good use of new technology and public interest to share important historic stories. The Twitter feed for UIL_transcripts can be found here. The website also provides insights into the phenomenon of "crowdsourcing," collaborative online projects that call upon the interest—and spare time—of members of the public to help transcribe historic documents. In this case, hundreds of people from around the world helped transcribe more than 15,000 pages of Civil War diaries and letters from the UI Special Collections.

Volunteers who logged into the site called up scanned images of handwritten pages from Civil War diaries and other documents. After deciphering the faded and sometimes hard-to-read writing, they entered a transcription into an online field and submitted it to staffers for review.

This month, libraries staff will expand and relaunch the website. Renamed D.I.Y. History, it will feature collaborative transcription for collections such as manuscript cookbooks and women's diaries, in addition to Civil War materials.